The Ultimate Guide to Homepages

How to think about, develop, and improve your homepage

Homepages are notoriously hard to write.

As companies grow, they expand in two different dimensions:

The product(s) get more and more features

Marketing targets more and more segments

As engineers rush to keep pace with the ever-expanding vision of the founder, marketers do their best to build messaging that resonates with each new customer type.

The end result? Your homepage likely isn’t quite as clear as it could be.

Introducing Anthony

Aakash here—If you’ve visited LinkedIn in the past year, you’ve probably seen Anthony Pierri in your feed:

Anthony is a prolific creator, and amongst tech’s foremost authorities on home pages.

So, I had to reach out to him about an opportunity to build the Product Growth Guide to Homepages with him.

Lucky for all of us, he agreed. So, without further ado, let’s get into it.

P.S. You can find more of Anthony at Fletch’s homepage, and on LinkedIn.

Today’s Post

What’s the purpose of a homepage?

The top 4 bad habits of homepage creators

Writing your ultimate homepage

Including:

How to choose your audience

How to position your product

Uncovering your key value propositions

Bringing your positioning & value propositions into a homepage

1. What’s the purpose of a homepage?

Every day, I check the Fletch company bank account.

But if I type mercury.com into Chrome and end up on the homepage (rather than inside the product), I am slightly annoyed — and you’re probably the same way.

Think about an app you use every day.

When was the last time you read their homepage?

This isn’t rhetorical. Your answer is probably “never!”

Ironically, the more you like a company, the less likely you are to visit or read their website.

If you don’t read it, then who does?

And what’s the point of a homepage?

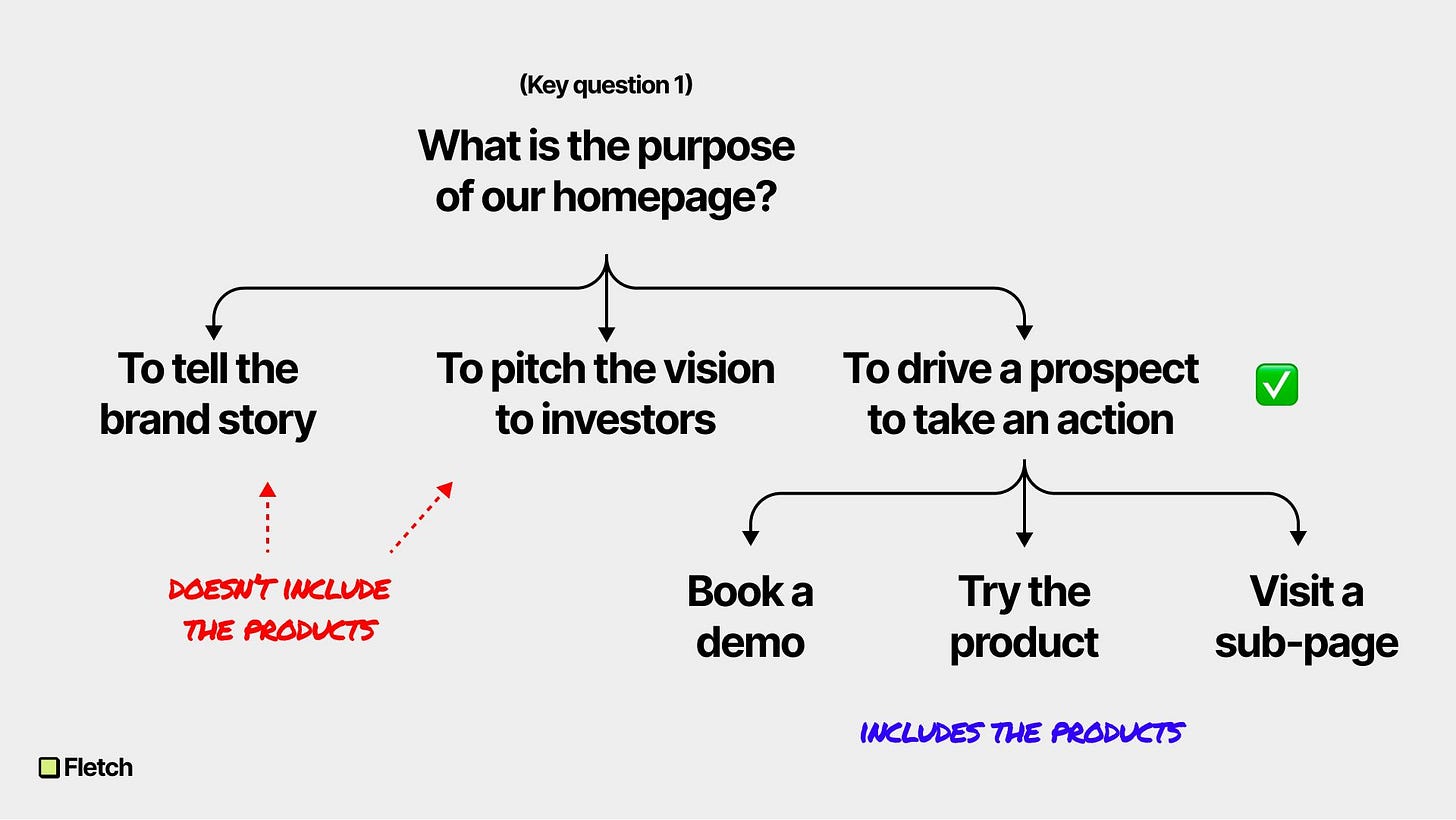

The Purpose of Your Homepage: Drive Potential Customers to take an Action

Your homepage isn’t your company Wikipedia.

It’s not the place to dump all your features.

It’s not the place to list every possible use case.

It’s not the place to cater to all of your market segments.

It’s a marketing asset—and likely your most-viewed web page—specifically designed for customers.

Not investors.

Not prospective employees.

Customers.

And homepages are meant to drive an action. After reading it, customers should either:

Book a demo (if you’re sales-led)

Try the product (if you’re product-led)

Or visit a subpage (where they then take a further action)

To get them to do one of these actions, you just need to be clear about what your product is and does, and who it is for.

Sounds simple, right?

Unfortunately, this super easy to mess up. As companies grow in size, their message clarity often deteriorates.

Take Slack, Airtable, and Zoom:

When I first posted the above image, I got tons of responses defending Slack’s messaging.

These responses fell into one of two buckets:

“Slack is trying to sell to the enterprise, so using vague language is strategic”

Let’s table this for now. But, know I think this is a bad argument. I’ll address it.

“Slack is so big it doesn’t matter what they put on their homepage!”

This also is a faulty argument.

Executives at Slack have shared that their TAM is roughly 1 billion knowledge workers. And depending on whose stat you trust, Slack has around 40m active users.

In other words, Slack has reached about 4% of their total TAM — with roughly 960m potential customers remaining.

The question is… does the vague messaging they have now make it easier (or harder) for the remainder of their market to adopt Slack?

If messaging gets less clear over time for most companies, what are the main reasons?

2. The Four Bad Habits of Homepage Creators

Four main bad habits that lead to vague/unclear messaging:

Speaking to multiple audiences at once

Choosing the wrong champion

Sharing multi-order benefits

Using vision-messaging

Bad Habit 1 — Speaking to Multiple Audiences at Once

The basis of (almost) all homepage messaging problems is the refusal to choose a target audience.

When marketers struggle to write compelling messaging, it's hardly ever a copywriting issue.

The problems usually result from trying to speak to multiple audiences at once… or no particular audience at all.

Read that picture again. Do you have any idea...

What company this is?

What the product does?

Who is it for?

This was on the 2021 homepage of Airtable, when it was worth billions of dollars. It was an incredibly powerful application that can be used by countless different companies for an endless number of use cases.

But the product's infinite flexibility creates a choice for the marketer:

Do I try to summarize the value and functionality for every potential segment?

Or do I choose one group as a representative example for the other potential segments?

Airtable—like so many high growth startups—made the mistake of choosing the former.

In the world of venture-backed startups, prioritization of any market segment is seen as an act of weakness.

By saying you're for one group, you're also turning away all other potential segments.

Reaching venture-scale requires going after all markets at once—or so the Silicon Valley Zeitgeist would have you believe.

Though we fundamentally disagree with this premise, it is the majority view in the world of SaaS startups—and the root cause of the widespread bad-messaging epidemic.

Bad Habit 2 — Choosing the Wrong Champion

A close cousin to Bad Habit 1 is choosing the wrong audience for your homepage.

There are two ways to mess this up: writing for an audience that is too senior or an audience that’s too junior (but hardly anyone goes too junior).

If you ask an early stage founder what persona they’re focused on, it’s almost always someone in the C-Suite.

“We’re targeting the CEO” (or CFO, COO, etc.)

Their thought process seems sound on the surface. If they can convince the CEO, then the sales cycle will be short and adoption will be wall-to-wall.

But choosing an audience that’s too senior causes two main issues:

1. There are exponentially fewer CEOs than VPs, directors, and managers

CEOs of mid-market and enterprise companies are notoriously hard to reach.

If your go-to-market efforts fail to penetrate their many walls of protection, then you’ll be S.O.L.

Say you want to sell into Salesforce.

Should you write the page for Marc Benioff?

Of course not.

2. CEOs aren’t buying software

Why do CEOs have VPs, directors, and managers?

One word: delegation.

Their direct reports are charged with figuring out the day-to-day decisions like:

“What CRM should we use?”

“What payroll software should we buy?”

“Should we get a new coffee maker in the break room?”

They do not spend their time surfing websites looking for new SaaS tools.

They aren’t taking daily or weekly meetings with account executives.

They don’t get bogged down helping move deals through procurement.

And while they may get pulled in at the final stages of a six, seven, or eight figure deal, they aren’t the “champion” of the deal cycle.

There is one exception: if you’re targeting a small business, there’s a good chance the C-Suite is still involved in day-to-day operations.

They’re still in the nitty-gritty decisions related to what software the company should use for each department (because they’re really “chiefs” in name only at this point).

Bad Habit 3 — Sharing Multi-Order Benefits

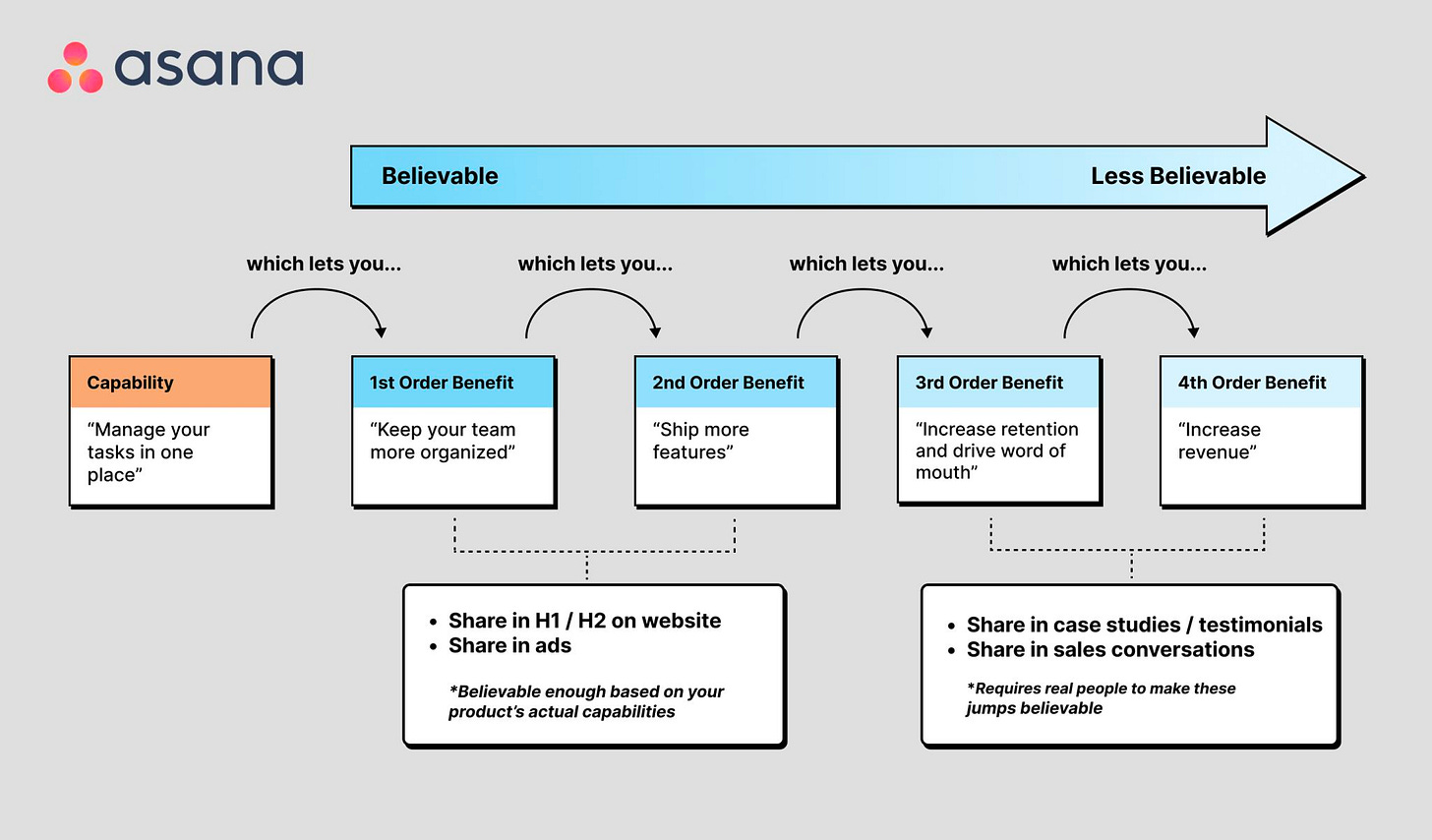

"Share benefits, not features" is the rallying cry of most marketers in B2B SaaS.

It's supported by another common phrase: "people buy a quarter-inch hole, not a quarter-inch drill," along with a meme about Mario.

But this begs the question — what exactly is a benefit?

To most, "benefits" are outcomes. If a customer adopts the product, the benefits are the outcomes they can expect to reach.

"Never forget your passwords again” (as in the case of a password manager) or “keep better track of your sales pipeline” (as with a CRM) are two examples.

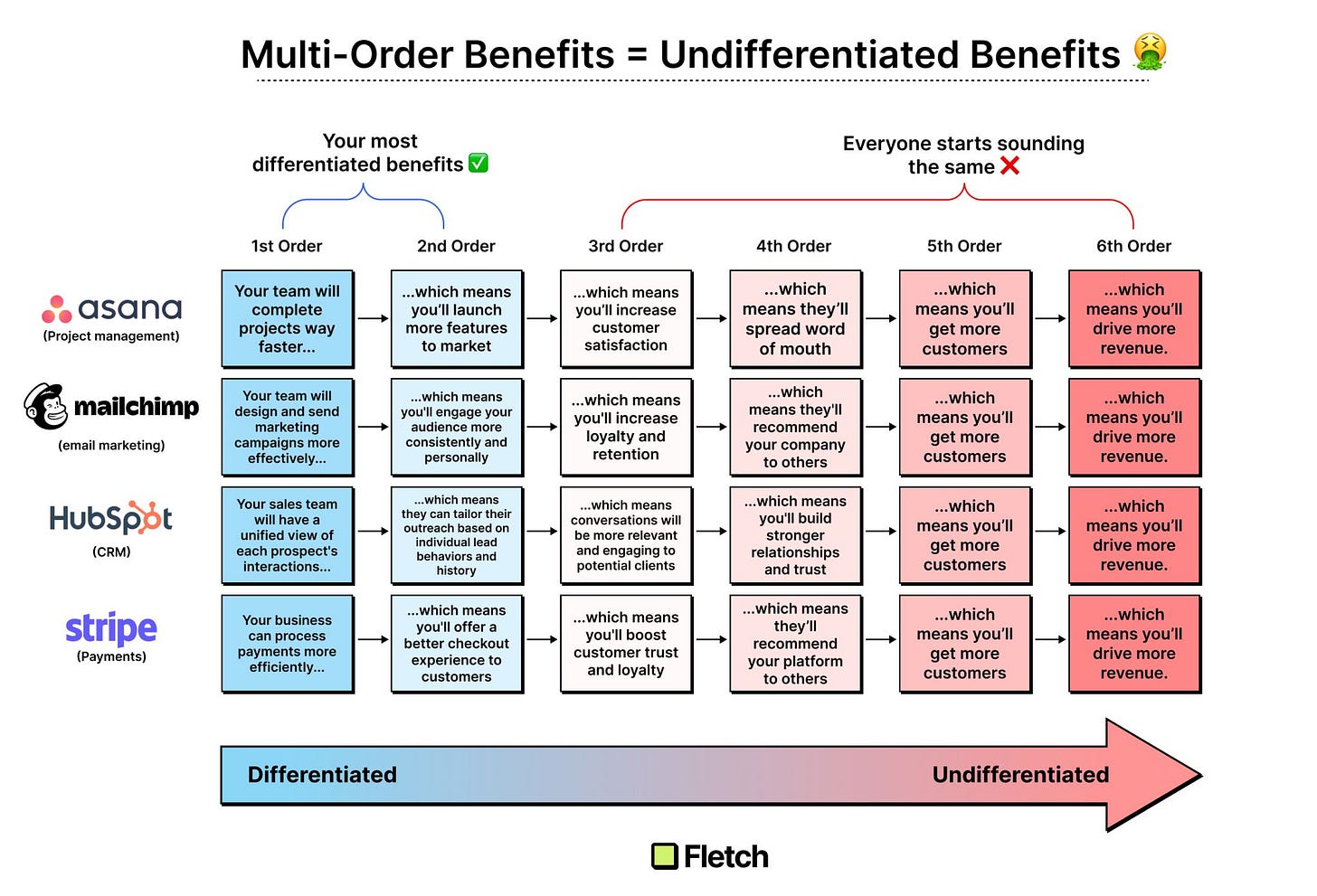

Benefits are also causal — meaning one benefit can trigger another benefit.

The first outcome that happens sequentially from using a product can be considered the “1st Order Benefit.”

That benefit may trigger a second benefit, or what we would call a “2nd Order Benefit,” which can then trigger another benefit, a “3rd Order Benefit” — and so on.

Ultimately, all benefits lead to either

Saving time

Increasing revenue or

Minimizing risk.

In a post-ZIRP (zero interest-rate phenomena) world when companies are collectively tightening their belts, talking about the multi-order benefit of increasing the top line became the focus for SaaS marketing teams.

The phrase "we need to talk about how our product drives revenue!" has since echoed across SaaS boardrooms everywhere.

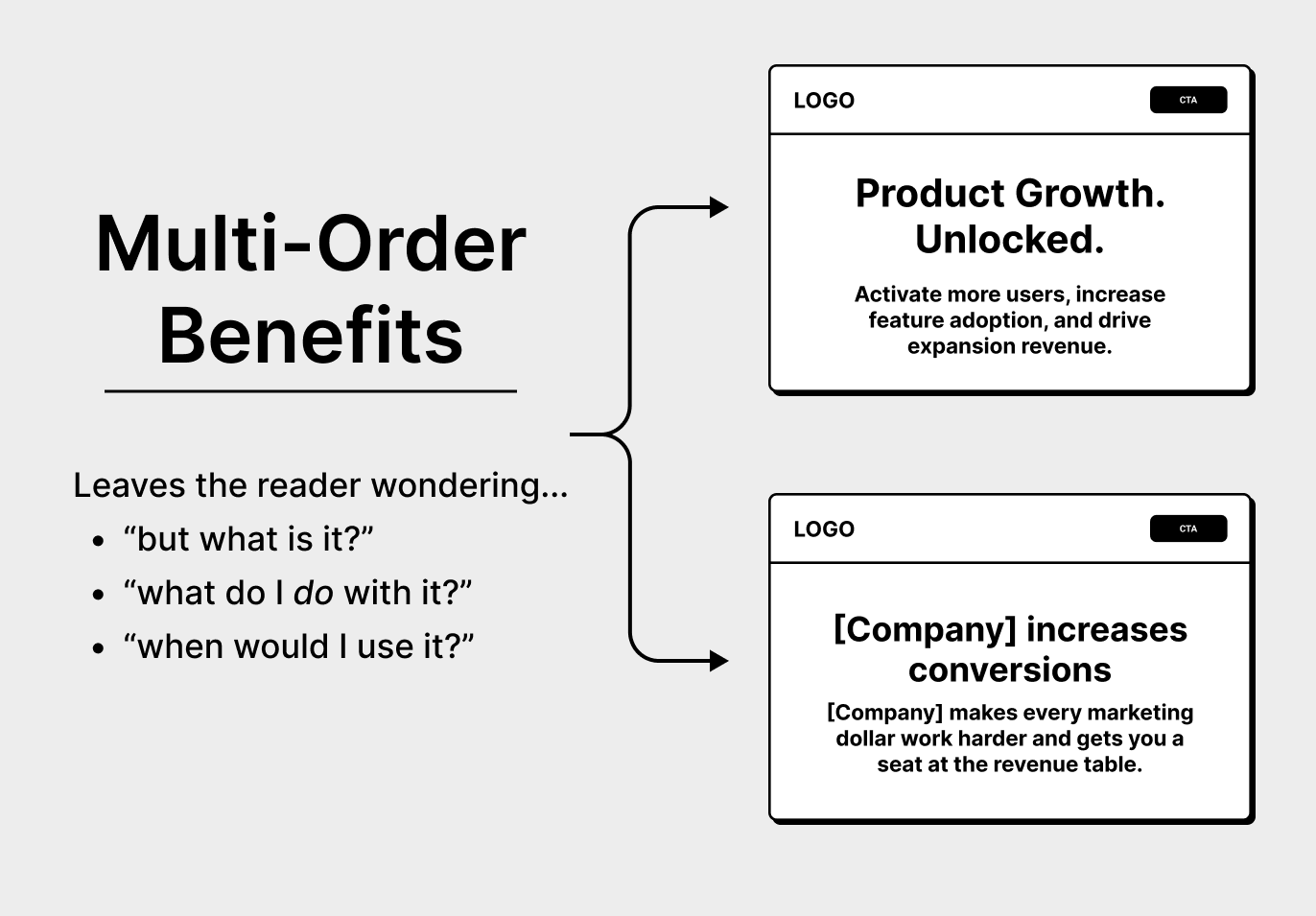

And gradually, SaaS homepages all started to look like this:

The focus on the multi-order benefit of “increased revenue” leads to four main issues for early-stage startups:

1. It hides what your product actually does

When you only lead with multi-order benefits, it actually obscures what your product does.

2. It removes your differentiation

If you say the same thing as everyone else, you make your startup infinitely harder to remember.

Customers won’t have the “mental availability” to recall your solution when faced with the problems that your solution solves.

3. It’s just not believable

Do companies believe that using Salesforce will increase their revenue? Yes.

Do they believe a seed-funded, no name 10-person startup can do the same? Unfortunately, no.

4. The audience that cares about increasing revenue isn’t shopping for software

This is what we talked about in Bad Habit #2!

The CXOs have delegated this.

So talking about revenue isn’t the right “why” for the actual decision-makers.

Bad Habit 4 — Using Vision-Messaging

Messaging lives on a spectrum:

On one end is the founder's vision.

On the other end is what the product does today.

These two messages are mutually exclusive.

And while there are some exceptions with mission-driven companies, 99.99% of companies don't qualify for this exemption.

The founder’s vision plays an incredibly important role in the company.

It gets investors and prospective employees really excited. Who doesn't want to work for a company that plans to change the world?

The mistake comes when you try give this message directly to customers.

In general, customers don't care about your vision.

When you lead your messaging with phrases like “Accelerate innovation through visual collaboration in the new hybrid workplace,” you put the burden on customers to figure out how and why they could use your product.

Now that we’ve gotten the bad habits out of the way… let’s jump in and re-write your confusing homepage.

3. Writing your ultimate homepage

Writing your homepage has four major steps:

Choosing your audience

Positioning your product

Uncovering your key value propositions

Bringing your positioning & value propositions into a homepage

We’ll cover them step by step.

Step 1 - Choosing Your Audience

Homepages are read by people.

Humans.

That work in departments inside of companies.

And have desires, fears, aspirations, etc.

Which means that all the normal rules of communication apply.

There’s no such thing as “writing a page for the enterprise.”

In the same way you can’t write a letter to your cousin, your grandma, your spouse, and your employer at the same time…

…you actually need to pick a primary audience (and yes, even for the homepage).

Segmentation (for Dummies)

What constitutes an Ideal Customer Profile (or “ICP” for short)?

There’s a telltale sign that someone doesn’t understand marketing if they answer that question with any of the following:

“Our ICP is the enterprise”

“Our ICP is Financial Services companies”

“Our ICP is sales teams”

These are all market slices — but they’re all incredibly broad to the point of being useless.

And they definitely don’t represent an ideal.

What about TAM/SAM/SOM?

This model is a good starting point… but is still too one-dimensional and doesn’t reflect the complexity and fragmentation of markets:

In reality, an ICP consists of a combination of firmographic, demographic, psychographic factors combined… along with specific scenarios and the pain that accompanies them.

Choosing your Ideal Customer Segment as your Audience

Companies have ICPs (whether or not they realize it or not).

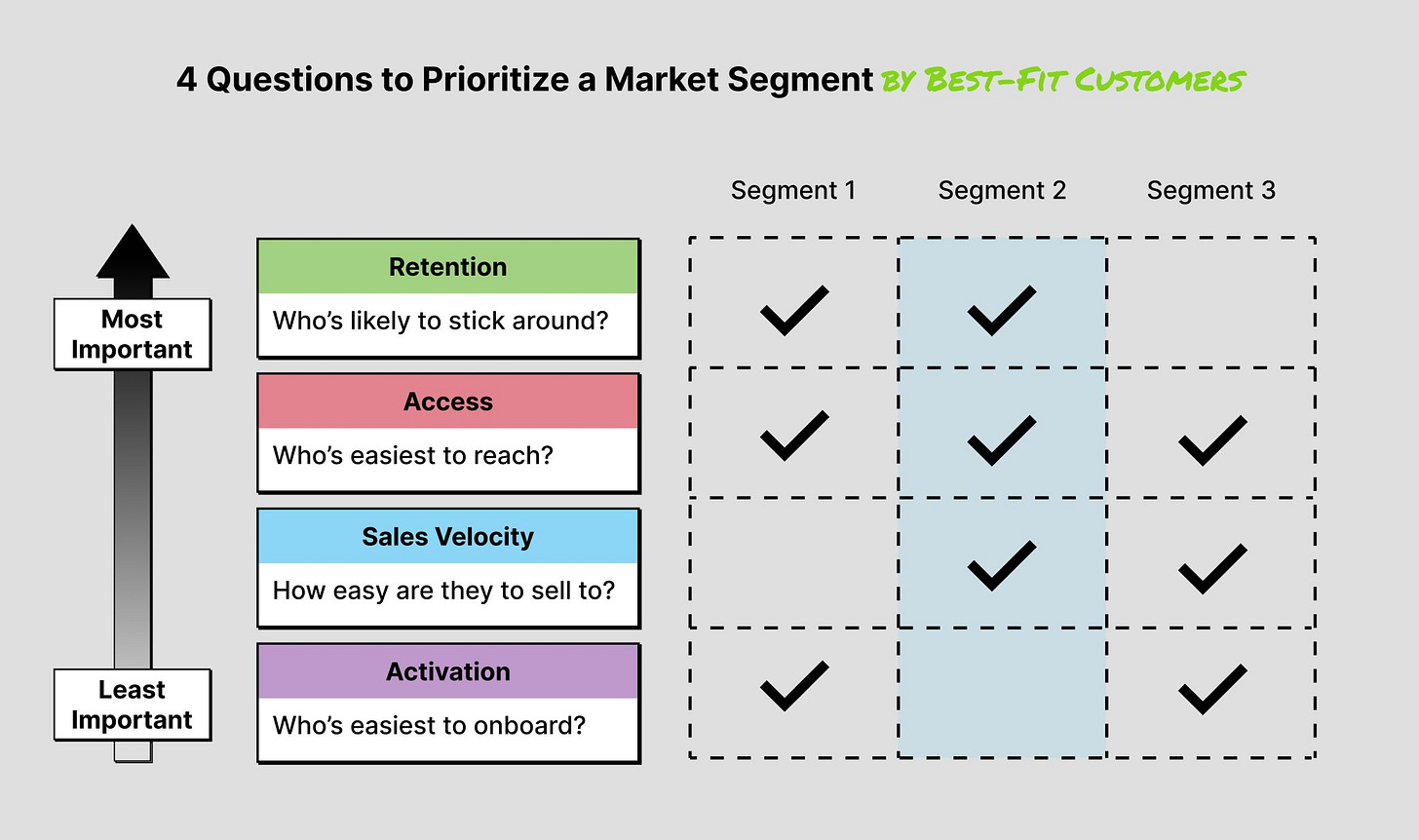

Certain segments should be prioritized for the good of the company.

They’re easier to reach, easier to close, easier to activate and monetize, and easier to upsell and expand.

A worthwhile exercise for leadership teams embarking on a homepage refresh should be to write down all the current (or potential) customer segments and rank them against each other.

The below is your start (but far from exhaustive):

What if you can’t choose?

Sometimes people accuse us (Fletch) of being too extreme in our advice of prioritizing one ICP at the expense of others.

But, in reality, this doesn’t need to be all or nothing. There’s ways you can retain prioritization without completely alienating the other segments.

Take the example of Uber.

They have four main target segments, and they simply list them in sequence by priority, devoting a section to each.

On the flip side, some companies can make a legitimate argument that their target segments are all equal in number and importance.

The way Rippling decides whether or not to add products to their suite is by dedicating a PM, engineer, and designer and empowering them to find product-market-fit with whatever they build.

Once they’ve found it, the product is added to the suite.

This, however, is the extreme exception.

All pre-product-market-fit startups do not meet this criteria and should not adopt this strategy on principle alone, as it creates tremendous friction on the end visitor to find what they are looking for.

Sometimes, the choice of homepage audience is made for you by nature of your go-to-market strategy.

Many software companies are seeking to reach end-users through a PLG motion while also going after the enterprise from a traditional top-down sales motion.

In this case, the homepage needs to focus on the end-user and the enterprise audience needs to get their own page (that can live prominently in the navbar).

The homepage plays a massive role in the PLG experience and focusing on the enterprise will effectively bottle-neck the entire PLG experience.

Step 2 - Positioning your Product

So now that you’ve chosen a target audience, the next question you must answer is:

“How do we want to position our product for them?”

Positioning is often needlessly complicated.

There are countless fill-in-the-blank, “mad-lib” style positioning statements that give the impression that positioning is like a complex math equation.

In reality, positioning just needs to answer two questions:

Who is your product for?

What is your product’s differentiation?

Our own (drastically simplified) math formula might look like this:

Positioning = Product Differentiation + Customer Segmentation

This equation can be referred to as “Minimum Viable Positioning.”

It contains the bare amount of information required to “position” a product.

As we’ve covered the market segment side of equation, let’s now turn to the product differentiation piece.

Choosing a Reference Point: Competitive & Contextual

If you want to talk about your product’s differentiation, you must answer… in relation to what?

Positioning requires a meaning reference point to explain how it is different and how it provides value.

There are two primary reference points, reflected in the below positioning strategies:

Competitive Positioning

With Competitive Positioning, you’re positioning against the current tool being used (”tool” here is a conceptual term, and can refer to non-software alternatives as we’ll demonstrate below.)

For example, Slack originally positioned against email:

They positioned Slack as a email-replacement rather than trying to differentiate against other messaging apps.

In some competitive framings, you do position against a direct competitor. Here’s an example from Around, a competitor to Zoom:

In a competitive framing, you’re naming an enemy that you’re seeking to replace.

The key is this enemy must be understood in the same way by everyone in your target market.

For this reason, positioning against “manual labor” would not fit under competitive positioning, because this phrase conjures up many different understandings from different customers.

Some might picture using an intern, others a spreadsheet, others a series of automations….

Conversely, positioning against “email” provides a universally understood frame of reference.

Talking about the downsides of “manual work” fits better within Contextual Positioning, which we will now cover.

Contextual Positioning

In this approach, your frame of reference is a common workflow or use case.

For example, SparkToro is positioned for the workflow/use case of audience research.

Contextual Positioning seeks to place your product into an existing workflow that is cumbersome or ineffective.

It says, “use us when you’re doing ______, and we make that process better/easier/faster.”

To see the differences in starker contrast, here are different ways Loom has positioned over the years (some contextual and others competitive):

How to Choose: Competitive or Contextual

When trying to decide whether to use a competitive reference point or a contextual one, the main heuristic is this:

Which makes it easier to talk about the value my product provides for my target audience?

The same product can be positioned in both ways, and it will generate different value propositions.

For example, consider the Arc Browser, a modern web browser created by the Browser Company.

If I use competitive positioning anchored against a competitor (i.e. “Arc is a replacement to Chrome”), then I’ll likely talk about features and functionality that improves on the weaknesses of Chrome (i.e. “Chrome is resource-intensive and bogs down your computer; Arc is extremely lightweight and will never cause a slow down”).

If I use contextual positioning anchored on a use case (i.e. “Arc is the perfect browser for writing research papers”), I’ll likely highlight features related to saving and organizing specific links and the information within them.

That’s positioning in a nut-shell.

It can be helpful to simply write out the options using the template below and evaluate each one by one.

Step 3 - Uncovering Your Key Value Propositions

Once you’ve chosen a target audience for the page and you’ve decided how you’re going to position for them (having chosen a competitive or contextual reference point), you’re now ready to actually make the argument that they should adopt your product.

These arguments are your “Value Propositions” — the value you’re proposing to the target customer that (ideally) they will pay you for.

Message Elements

There are six essential components to a value proposition:

1) Use Case: this is the collection of activities your customers are undertaking

2) Current Tool: this is what they use to perform these activities today (without your product in the mix)

3) Problem: this is whatever is preventing them from making progress to accomplishing their use case

4) Capability: this is action the customer can take with your product

5) Feature: this is part of the product that makes the capability possible

6) Benefit: this is the outcome of applying the capability to the use case

See the example below for PandaDoc, a contract management tool:

Value Proposition Canvas

Now that you have the messaging building blocks in place, we want to apply these to our product, market segment, and positioning approach.

If you’ve chosen a competitive positioning approach, you’ll want to craft value props related to problems of the alternative tools:

This example uses our own company Fletch, and shows why we are best positioned to help early stage startups — when compared to the other “tools” (i.e. copywriters, generic marketing agencies, and your internal team).

If you’ve chosen a contextual, use case-based positioning frame of reference, then you’ll want to fill out the below canvas:

As you now will note, the problems are associated with specific steps at completing the use case of writing a homepage.

The detail-oriented observer will notice that some boxes are grayed out.

The canvas allows for the flexibility of address several audiences at once, along with different use cases and tools.

For the vast majority of companies, we would avoid using these boxes and seek to keep the message as focused as possible.

Step 4 - Bringing your Positioning & Value Propositions into a Homepage

I'm not a big believer in one-size-fits-all templates.

That being said... 80% of early stage startups would benefit from adopting this exact homepage structure.

This is an example page from a company called eWebinar.

The sections loosely mirror what you might say in a sales call:

Hero

This is where you first "position" the product

The goal is to include as much basic information as possible—without being too hard to scan—that will answer all the key questions: i.e. what is the product, who is it for, what use case does it address, etc.)

This is also the place to build credibility by sharing the logos your target customers would recognize and trust

Problem Section

It's here that you call out the problem your prospects are experiencing

The vast majority of early stage startups don't do this... because they haven't actually picked a target customer

This builds tremendous empathy and attracts your best fit customers while turning away bad fit leads

Solution Intro

Once you've dug into the pain, you now transition back to your product

It's here that you can include any info you couldn't fit into the hero to reinforce the positioning

Value Propositions

This is where you get into the specifics of HOW your product actually solves the problems mentioned above

You should be talking at the feature/feature set level, along with the accompanying capabilities and benefits from each

And that’s it! You’ve completed the 4 steps to create your ultimate homepage.

Additional Resources

Up Next

Aakash Here—I hope you enjoyed that deep dive from Anthony as much as I did! Be sure to give him a follow.

Thanks so much for accommodating my vacation last week. I’m back in action, and very excited for what we have coming up next:

Guide to consumer pricing models

How to be a great case interviewer

Trouble-shooting outreach

It should help product leaders, PMs, and aspiring PMs alike.

Talk to you soon 🍻

Aakash

Probably the best resource on the internet on building a compelling home page. Props to Anthony and Aakash.