👋 Hey Everyone: Aakash Here. I hope the Holidays are treating you well.

Today, I’m sharing a guest post by Ed Biden. It’s a great showcase of the quality content he is producing at Hustle Badger. Check it out!

Without further ado…

What is a strategy?

A product strategy explains what you will work on, and why. It links the day-to-day work that you are doing to the big picture company strategy and vision.

Most helpful for PMs, it provides a clear rationale about what you are NOT going to do. It’s easy to get drowned in requests from users and various stakeholders around the business. Everyone has a great idea or a pressing question that needs answering.

But not all these requests will be worth doing. Some might be great ideas, some might be ok, and a few will probably be counter-productive. Assessing each one-by-one would take a huge amount of time.

You need an approach that allows you to consistently work on high impact features, without going back to first principles on every idea. This is the essence of what a product strategy is.

A product strategy is your plan for creating the most value possible for your users and your company. And you do this by focusing your time on a small set of really high impact work, rather than diluting your efforts across all the different things you could potentially do.

Good product strategies therefore have two core features that allow you to create amazing value for your users:

They are composed of high impact work

They are mutually reinforcing

That is to say, of all the pieces of work that you could do, product strategies choose ones that create more value in a shorter amount of time. But not only that, they also choose pieces of work that when combined create more value than the sum of their parts.

Strategy is never done

A lot of people think creating a strategy is something that should be done on a periodic basis, after huge amounts of research and analysis.

Whilst having a solid evidence base for your strategy is undoubtedly good, creating a strategy is much better thought of as an ongoing activity, rather than an ad hoc task.

“When I start a new job, I define a SWAG (Stupid Wild-Ass Guess) product strategy within my first two weeks.”

– Gibson Biddle, ex VP Product Netflix

You really need a working understanding of what your strategy is at all times. You want to start with a basic hypothesis as soon as possible, and then strengthen this over time. This approach several benefits:

It’s easier to get feedback from stakeholders when they have something to comment on

You can focus your discovery by seeing where your evidence is weak

You can use your hypothesis as your strategy whilst you firm things up

As you ship features, engage with stakeholders, and do more discovery your strategy will naturally shift. That’s fine and normal.

It’s almost always better to get going and course correct as you go along, rather than do nothing for several weeks before acting.

The rest of this article is a guide to developing a strategy whatever timeframe you’ve got:

1 Day | Snap Strategy - pulling together your initial structure and thoughts

1 Week | Working Hypothesis - building that out to a reasoned narrative which you can test

1 Month | Product Strategy - refining that into a well-evidenced strategy that clearly articulates where you should focus

The longer you spend on your strategy, the more you can reduce uncertainty, but you can never remove it completely, and navigating this ambiguity is a core skill you need to master as a product manager.

7 steps to create a strategy

Regardless of the timeframe you’re working to, then a solid product strategy has 7 major sections:

Objective - what is the challenge we are responding to?

Users - what does our audience need?

Superpowers - where can we create unique value?

Vision - what is the future we are building?

Pillars - what are the main themes of work to get there?

Impact - does our planned work meet our objective?

Roadmap - what are we doing next, and how do we share progress?

As with product development itself, you’ll find that this isn’t a linear process. As you go through the steps you’ll learn more, and want to update earlier steps. This fits naturally with the fact that creating a strategy is a continuous activity, rather than a one-off effort.

We’ll run through each of these sections in turn, answering:

What are we talking about?

Why is it important?

What might your Day 1 / Week 1 / Month 1 answer look like?

Hustle Bader has also created a product strategy template that you can use to create your own strategy.

Objective

Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

The Cheshire Cat: “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I don’t much care where.”

The Cheshire Cat: “Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go.”

- From Alice in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll

Without a definition of success, a strategy is meaningless. You can’t go somewhere “better” or “faster” if you haven’t defined where you’re trying to get to.

Strategies are always the response to a challenge. They answer the question: “what is the best way to do X?”. Without “X” there is no yardstick for impact, so selecting the highest impact work is nonsensical.

It’s usually helpful to define your objective both quantitatively and quantitatively. A great format is:

Objective = mission + measure

Mission - an inspiring statement of your purpose

Measure - a hard metric that gauges the progress you’ve made

Mission

Writing down what you’re trying to achieve in words helps you define success, and it’ll be much easier to pick the right number to measure progress once you’ve done this. Words also provide a richer description than metrics, and inspire people in a way that metrics alone cannot.

Examples:

Provide a frictionless onboarding process

Create a secure and streamlined check out

Demonstrate the full value of our product as fast as possible

Help users find the perfect product for them

Give creators the insights they need to thrive

Measure

Whilst missions are great for pulling your thoughts together and inspiring people, on their own they give no sense of where you’ve started, where you’re going or how much progress you’ve made.

A good solution here is to set yourself a target in the format:

Move [metric] from [baseline] to [target] by [date]

Examples:

Increase ARR from $125m to $150m by the end of 2024.

Increase day 30 retention from 18% to 22% by the end of Q3.

Decrease returns from 10% to 7% by 30th October 2024.

What this looks like

Out of all the sections we’ll cover, your objective will likely change the least over time. This is especially true if you’ve inherited an objective from an existing team, or have been set your objective by the CEO or a senior product leader.

Day 1

If you haven’t been set an objective by someone else, then creating one yourself is the first thing to do. This will determine how you approach the rest of your strategy. You can get going here by:

Having a kick-off meeting with your boss to understand their current thinking.

Looking at what the most recent OKRs or internal goals were.

Digging out the latest All Hands that set a direction or strategy for the company or product org.

Digging out the latest company strategy, and any recent functional strategies (e.g. product strategy, marketing strategy).

Draft both a mission and define a measure in the format above as your starting point.

Week 1

With more time, you can firm up your objective by doing the following things:

Showing your Day 1 draft to stakeholders for feedback

Thinking through your measure in more detail to check if it's the right metric.

When thinking about the measure, it’s good stress test the metric you’ve picked by asking yourself:

If we made progress against our mission, would this metric obviously move in one direction?

Is this metric easy for people to measure and understand?

Is this metric relatively stable if we don’t do anything?

Is this metric in the control of my team?

What is the right time period to measure this metric over (e.g. is daily active users or weekly active users a better measure)?

Your objective will still have the same format as in Day 1, but you should feel more comfortable that you’ve captured it in the best possible way.

Month 1

Hopefully you can come up with a solid objective in Week 1, and this won’t change much with more time. If you are working on a particularly ambiguous problem space though, then you might want to spend a bit more time working out what the best metric to measure is.

For example, if you’re trying to maximize customer activation, then how do you define activation, and what is the best metric to measure this?

Each case here will be slightly different, but ideally you can justify the measure you are using with some evidence.

Example

Mission: Maximize customer activation

Measure: Number of users performing 20+ searches in first 3 days

Rationale:

Users who perform 20+ searches have 45% probability of spending $200 on site (i.e. meets our definition of a high value customer), vs. 2% probability of users who perform <20 searches

This metric was the strongest predictor of whether a customer goes on to spend >$200 out of the 15 metrics we analyzed across 5 different time periods (D1, D3, D5, D7, D14).

We didn’t look at metrics beyond D14, as this wouldn’t be responsive enough for our needs

Users

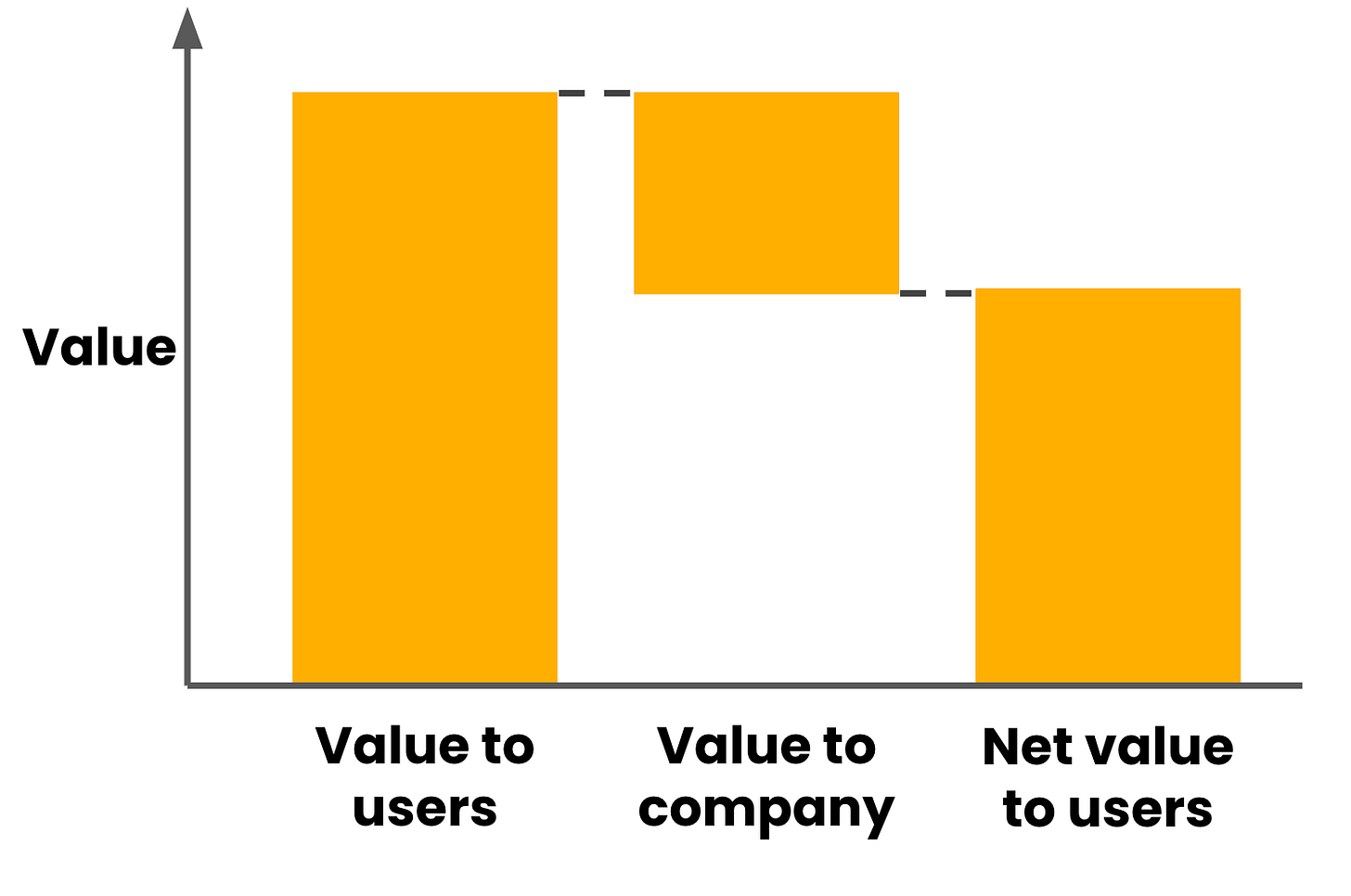

With the objective set, you’ve defined the question you need to answer with your strategy.

That answer will depend on a good understanding of your users. Business value can only be created when you create so much value for users, that you can “tax” that value and take some for yourself as a business. If you don’t create any value for your users, then you can’t create value for your business.

Whilst there are many ways to understand what your users will value, two techniques in particular are incredibly valuable, especially if you’re working on a tight timeframe:

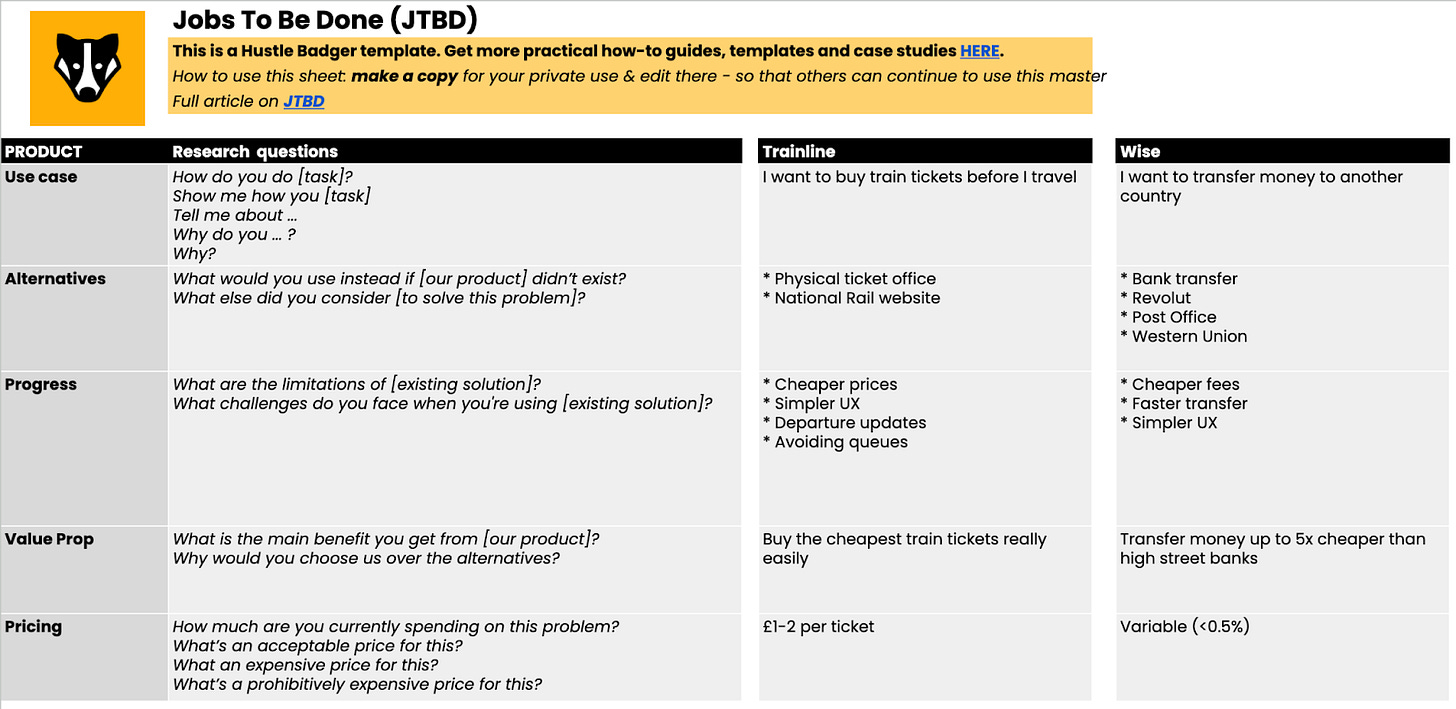

Jobs To Be Done - what your customers need, where they are struggling, and how they define progress

Customer Journey Mapping - the flow that your customers go through to achieve one of their needs, and how their thoughts and feelings map onto that flow

Jobs To Be Done (JTBD)

“People don’t simply buy products or services, they ‘hire’ them to make progress in specific circumstances.”

– Clayton Christensen

The core JTBD concept is that rather than buying a product for its features, customers “hire” a product to get a job done for them … and will ”fire” it for a better solution just as quickly.

In practice, JTBD provides a series of lenses for understanding what your customers want, what progress looks like, and what they’ll pay for. This is a powerful way of understanding your users, because their needs are stable and it forces you to think from a user-centric point of view.

This allows you to think about more radical solutions, and really focus on where you’re creating value.

To use Jobs To Be Done to understand your customers, we’d recommend thinking through five key steps:

Use case – what is the outcome that people want?

Alternatives – what solutions are people using now?

Progress – where are people blocked? What does a better solution look like?

Value Proposition – why would they use your product over the alternatives?

Price – what would a customer pay for progress against this problem?

Worked example of JTBD, including user interview questions to ask

Customer Journey Mapping

Customer journey mapping is an effective way to visualize your customer’s experience as they try to reach one of their goals.

In basic terms, a customer journey map breaks the user journey down into steps, and then for each step describes what touchpoints the customer has with your product, and how this makes them feel.

The touch points are any interaction that the customer has with your company as they go through this flow:

Website and app screens

Notifications and emails

Customer service calls

Account management / sales touch points

Physically interacting with goods (e.g. Amazon), services (e.g. Airbnb) or hardware (e.g. Lime)

Users’ feelings can be visualized by noting down:

What they like or feel good about at this step

What they dislike, find frustrating or confusing at this step

How they feel overall

By mapping the customer’s subjective experience to the nuts and bolts of what’s going on, and then laying this out in a visual way, you can easily see where you can have the most impact, and align stakeholders on the critical problems to solve.

What this looks like

Day 1

On Day 1 you should be able to run through the 5 sections of JTBD and sketch out a quick customer journey map, but you’ll only be able to populate it with the information you already know and your intuition.

Ideally you’ll have spent some time reading any existing user research that is available, but if not, then running through the user journey yourself whilst you empathize with your customers is good enough to start.

Don’t worry about this being 100% accurate right now - by writing down what you already know and what you suspect is true you are creating a structure for later, and map for the discovery you need to complete.

Week 1

After Week 1 you should have some more meat on the bones of your JTBD and customer journey map, and be able to back up what you’re saying with some of your own research.

For the JTBD framework then you should have spoken to a handful of real customers and asked them what they think. Whilst this won’t be in any way statistically significant, you should get a sense of whether the main use cases you’re describing resonate with users or not.

On the customer journey map, you can use the same customer interviews to add more detail about how people think about the journey. Get them to walk through it and describe how they feel along the way. If there are quotes that really encapsulate the user’s perspective, then pull them out and add them to your map. You should also go back through the flow yourself, and double check you haven’t missed important touchpoints (e.g. emails or calls that product is not responsible for, but play an important part of the customer experience).

For both the JTBD and customer journey map, you should also be able to show your initial thoughts to other stakeholders and get their feedback. As well as their judgment on what are the core needs that users have and challenges they face, you will likely remind them of other research and analysis that’s already been done and you can use.

Month 1

After Month 1 you should have started to quantify the insights you sketched out in your first week.

Ideally you’ve not only spoken to 10-20 users yourself. You might also have run (or be in the process of running) a survey that asks a large number of respondents (>100) about what alternatives they use, the qualities of a better solution to their use case, and what they’d be willing to pay for this.

Finally, you could consider adding in-product feedback loops so that you know how individual steps of the journey perform, or looking at other quantitative signals that give you a good indication of the user experience.

Superpowers

Having established what your users want, you now need to figure out how you can offer them an exciting solution that they will value. Whether you’re a startup or an established enterprise, this should stem from your unique superpowers.

Your superpowers are the things that you can offer, but other companies will find very difficult to replicate. This is important for a few critical reasons, as unless you have a value proposition that other companies can’t copy:

It will be difficult for your marketing to cut through the noise. There will be nothing special or unique about it.

You won’t be able to delight users, as they’ll consider the benefits you offer commodities that anyone can give them.

Your margins will decrease, as you will need to drop prices and spend more on marketing to stand out and attract customers.

Mature digital companies aim for 20-30% net margins and growth rates of >25% y-o-y. This is what supports their high valuations. These sorts of numbers just aren’t possible without a strong competitive advantage (i.e. superpowers).

If you’re working on a strategy for a whole product, then the superpowers that you might have can be split into 7 categories:

Network effects – Each user enjoys more value as new users join the network

Scale economies – Unit costs decline as volume increases

Switching costs – Switching to an alternate product would be costly or painful for users

Counter positioning – Where a new product’s business model or value proposition cannot easily be copied by incumbents as it would damage their existing business

Cornered resource – Unique access to a valuable asset

Branding – An objectively identical offering has higher perceived value

Process Power – Embedded company culture and process which enable lower costs and/or superior quality

If you’re only responsible for a part of the user experience, and not the whole thing, then you should think through the core benefits you can offer users (i.e. the value proposition from JTBD), and how you can reinforce these benefits in ways that competitors will find difficult to replicate.

This can take the format:

[Imagined feature] might offer [core customer benefit], whilst being difficult to copy because [hard-to-copy superpower].

Example

Smart locks on home dramatically improve guest experience (never lose key) and host safety (change code for every stay). This is difficult for competitors to copy because integrating hardware and software at scale and cross-platform is a huge task.

Revamped ratings and reviews make it easier for guests to find the best places to stay, and encourage hosts to provide a great experience. This is difficult for competitors to copy because it relies on a significant volume of stays.

What this looks like

Regardless of how long you have to spend on your product strategy, how you articulate your superpowers is likely to look roughly the same: 2-3 sentences that describe the superpowers you have, or types of features that will create user value and be hard for customers to copy.

Day 1

On Day 1, you can start hypothesizing what these superpowers might be based on your understanding of competitive theory and what sort of company you are working for (e.g. marketplace vs. SaaS).

Week 1

After Week 1 you should have some feedback from stakeholders (including your team) on what the best superpowers to focus on should be. You should also have spoken to some real users and asked them about where they see the key benefits of your product, which no one else can offer.

Month 1

After Month 1 you should have been able to test your value proposition and the unique benefits that you offer on lots of real customers (10-20 interviews, potentially a quantified survey). This should give you a very strong indication of where to focus.

Vision

Maybe you’ve heard the story of the three bricklayers. They are asked what they are doing, and the first one answers: “I’m a bricklayer, I’m working hard to feed my family.” The second answers: “I’m a builder, I’m building a wall.” And the third answers: “I’m a cathedral builder, I’m building a cathedral.” The same work is given different meaning through a clear vision that is inspiring.

Having a clear vision helps you link the day-to-day work of your team to a grander purpose. It helps you inspire the people around you, and align them on what you are trying to achieve.

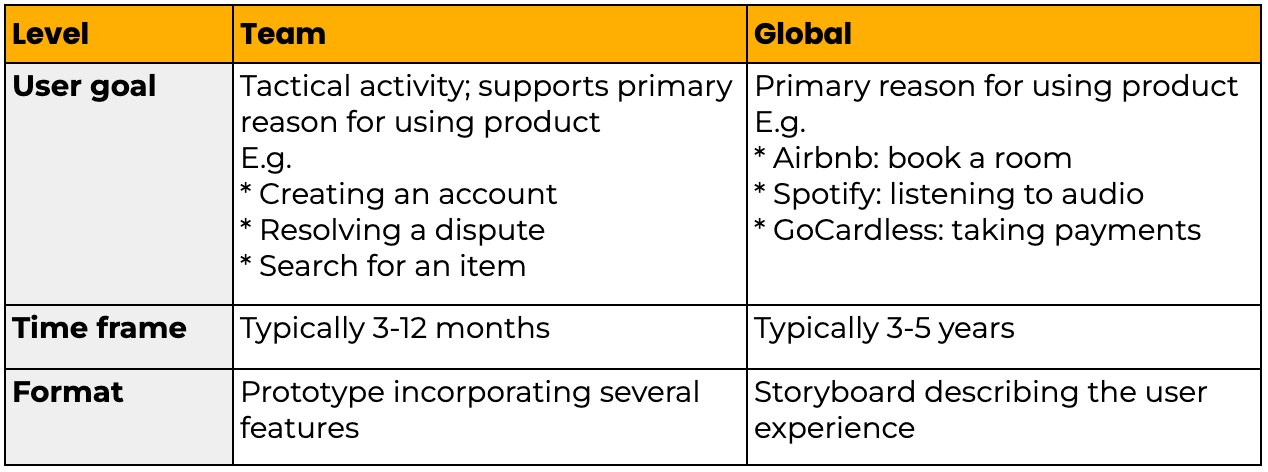

People talk about “product vision” in different ways, and may be referring to:

A 1-line vision statement

A set of product principles

A product vision board or business canvas

Amazon style PR / FAQs

A series of mockups or storyboard, a “visiontype” (from vision + prototype)

“There’s something about seeing the user experience that turns the light on…aha, I get it.”

– Jeff Middlesworth, Chief Product Officer at Emma

We think there’s something special about creating a vision that people can see, and prefer the visiontype version. It inspires teams and clarifies what you’re aiming for in a way that written documents cannot. It’s the approach championed by companies like Airbnb with their Snow White project and Sana.

Practically speaking, this is a series of mockups, an interactive prototype or a storyboard that shows the key moments in the user journey, and may be annotated to call out particular features, company capabilities or user feelings.

As with product strategies themselves, both companies and teams have visions at different levels, and these feed into each other. These have different scopes and goals - at a company level you’re trying to communicate where the product is going as a whole over the next 3-5 years and align multiple teams, whilst at the team level you’re trying to provide a clear view of what you’re building over the next 3-12 months.

The company vision will be a compilation of each team’s individual visions, whilst the team vision will show at a higher level of detail what their part of the user experience will look like.

For both, you can create these by reverse engineering the customer journey map:

Introduce the target user and their needs

Identify the key steps in their journey that you want to highlight

Imagine how they should feel at each of these core steps

Describe the sort of experience and touchpoints that would make them feel this way

In other words, you think back from the feelings you want your users to have to the features and touch points you need.

What this looks like

Day 1

On Day 1, you’re not going to have time to come up with visuals or get much input from other people. But to get going and develop a hypothesis for what the vision might look like you can synthesize what you know about the user journey into bullet points that outline the key moments that the vision should show, and what customers should feel like at each of those moments.

Week 1

After Week 1 you should be able to pull together 3-4 high level sketches or mockups for the key moments in the user journey (assuming you have design capacity!). You should also have had time to show these mockups to key stakeholders and the team to get their input.

Month 1

After Month 1 then you should have had enough time to do a number of user interviews (perhaps 10-20), pull together other insights, and run a workshop where you can co-create a product vision with other key stakeholders. That should allow you to create a vision that is closer to a storyboard or interactive prototype, which has plenty of buy-in from everyone involved.

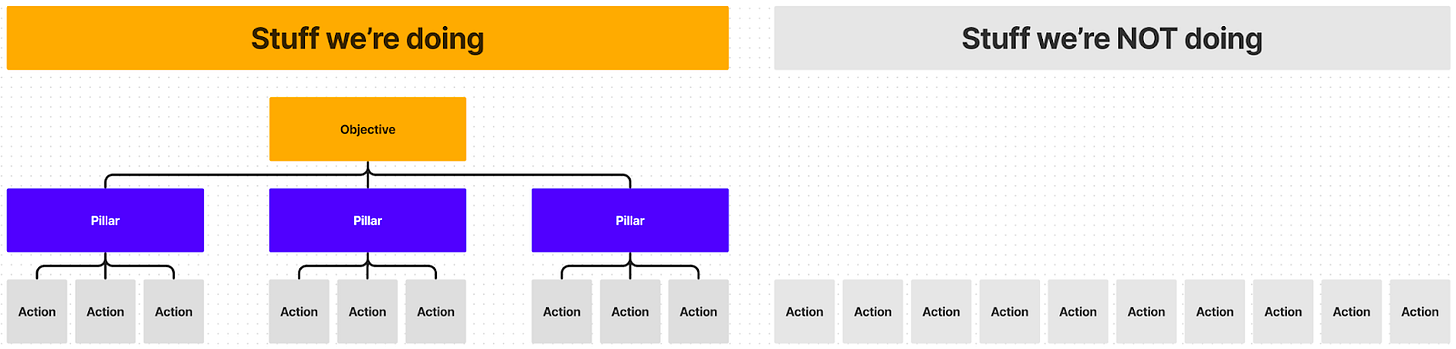

Pillars

Once you’ve set your vision, then it’s time to think through what are the key themes of work that will comprise your strategy. These pillars are really the heart of your strategy, outlining the work that will take you from where you are today, to where you have described with your vision.

Most product strategies end up with 2-4 pillars that say where you’ll focus your efforts. The work inside these pillars should be high impact and mutually reinforce the other product pillars as well as work by other disciplines. Together they should solve your users’ needs, reinforce your competitive advantage, and deliver on your vision.

As we’ve discussed though, by being really clear about where you will focus, you’re naturally being really clear about where you won’t focus. That means defining your pillars can bring tensions to the fore, as stakeholders who in principle agree with the overall strategy are loathed to let go of pet projects that don’t fit.

Here it’s better to lean into the tension and have the difficult conversations up front. Fudging things at this point will only cause you more pain further down the line when it becomes clear you’ve over committed. Ultimately you can only do as much work as you have engineering capacity for, and promising people more than this is going to lead to much more difficult conversations in the future when you can’t deliver.

What this looks like

Day 1

On Day 1 your pillars will consist of 2-4 workstreams, each with a title and a one sentence description. These you can pull together from looking at existing strategy docs, and thinking through the main gaps between your Day 1 understanding of the customer journey, and your Day 1 vision. Remember this is just a hypothesis to build on and get feedback on. You’ll be adding a stronger rationale for why you’ve picked these pillars over time.

Week 1

After Week 1, you should be able to flesh out your pillars further, adding a few bullet points of justification to each pillar, outlining the insights and assumptions that underpin it.

By this point you should have some feedback from adjacent functions (e.g. marketing, customer success) so your strategy can dovetail with theirs. You should also incorporate any changes that you’ve made to your understanding of the customer journey and your vision, so your pillars still outline the work you need to do to bridge the gap between the two.

As you start to pull together evidence that supports why you’re working on these pillars, reflect on how strong your logic is. Any weak spots you’ll want to reinforce over time by doing more discovery.

Month 1

After Month 1, your pillars will still look broadly the same as they did after Day 1 and Week 1: 2-4 workstreams with a title and one line description. The main difference will be that you should have quantified what progress in each pillar looks like, by defining a metric for it.

The big change will be in the number and quality of insights that support your pillars though. Here you should probably have several charts, slides or other compelling pieces of evidence that your pillars are the right things to work on. You don’t need 100s of data points here - typically a handful of killer insights is much more effective than drowning people in information, but you need enough to convince everyone (yourself included) that you’re on the right track.

Don’t forget that within your first month you’ll likely have started to ship features and be able to see their impact in the wild. There’s no better data to shape your strategy.

Impact

As you pull your pillars together, it’s a good idea to estimate the impact that you think each of these workstreams can have. You can’t forecast this completely accurately, but going through the process of modeling the impact you expect will help you sense check you’re working on high impact features, and reduce the risk you’re taking.

Estimating the impact of features is as much art as science, but typically involves:

Developing a narrative for how your pillar will create impact

Expressing that narrative as a driver tree

Estimating the change in driver metrics from the baseline you’ll see

Example - BackMarket

Step 1 - Narrative for impact

If we increase visitors to the website, and conversion through the funnel remains constant, then this will result in more transactions and higher revenue.

Step 2 - Driver tree

Step 3 - simple model with baseline and targets

When you’re estimating the uplift, you can’t know for sure what will happen, but a good starting point is to do one of the following:

Look at how easy it’s been to move this metric in the past

Look at the difference between your best and average cohorts here

Estimate the change you can make to the nearest order of magnitude

None of these methods will be 100% accurate, but the point here is not to predict exactly what will happen. It’s to think through what’s possible or even probable. You don’t want to commit to pillars that have no plausible mechanism for generating the impact you want. You want to focus on features where even modest and very believable improvements will deliver significant business impact.

What this looks like

Day 1

On Day 1, your impact estimates won’t be quantified. At this stage just think through the narrative that describes how your pillars create impact. You can do this from a basic understanding of the conversion funnel.

Week 1

By the end of Week 1 you should have gone past the driver tree stage and been able to build a simple spreadsheet model with some data that is either high level estimates or real data. Either way, you’ll start to understand the key assumptions you’re making, and potentially which drivers are more important than others.

Month 1

After Month 1, then you’ll still have a basic spreadsheet model, but the quality of data you can input into it will be much stronger. Ideally you can look at historical releases or the difference between user cohorts to size the opportunity. Failing that, you will need to estimate the uplift you’ll see to an order of magnitude.

Don’t get sucked into the details too much though - remember the goal here is not to come up with the perfect answer, but to develop a robust understanding of how you’ll create impact and what would need to be true for that to happen. You want to avoid working on pillars that seem good in theory, but have no plausible mechanism for creating business value.

As you go through this process, be open to rethinking your vision and pillars if the work you have planned doesn’t add up to the objectives you’ve got. Ignoring what the numbers are telling you and hoping for the best is not good strategy. If necessary, have the difficult conversations up front about what your options are, and where else you might focus.

Roadmap

Once you’ve developed your pillars and sense checked that these can deliver the impact you’re looking for, what’s left is to actually start executing. You’ll need to:

Come up with feature ideas

Prioritize the order you’ll build these features in

Learn and iterate as you ship features

Keep everyone up to date on progress as you go

Whilst the details of how you manage this will vary from team to team, you’ll probably use some sort of roadmap or backlog.

Before rushing to reuse your last roadmap template, have a think through:

Audience - who do you need to keep informed? What are their needs?

Confidence - how certain are you about what you’re putting on the roadmap?

Format - what is the best communication channel and cadence to keep everyone updated?

Ultimately what you’re trying to do here is give everyone a visibility on what you’re planning to do, whilst being transparent about the level of ambiguity you’re navigating.

Stakeholders may well want more certainty than you can immediately give them, but taking a stand on a particular format for roadmaps and updates doesn’t help anyone. Now / next / later, gantt charts and everything in between has its place under the right circumstances. Instead it’s better to work with your stakeholders to understand their needs, and to co-create a lightweight method of reporting that works for everyone.

What this looks like

Day 1

On Day 1 there’s no point getting into the nuts and bolts of creating a roadmap. All you want to do at this stage is have a list of ideas that have come up, so you can make your pillars a bit more tangible and don’t forget anything.

This list of ideas will come from any existing ideas the team has, the expectations you’ve been given by your manager and your personal product sense and intuition.

Week 1

After Week 1 you should start to be able to add more structure to this list, and have a loose order you can work from, even if you expect it to change significantly as you go.

It’s a good idea to include the team in brainstorming ideas for the backlog in the first week or two as well, so they feel they have had a stake in creating it, and therefore have more buy-in.

Month 1

After Month 1 your roadmap should be up and running in a steady state. Typically here you’ll have up to 3 months of work with a fairly fixed sequence, and solid evidence behind why and how you’ll build each feature.

Your work 3-6 months out will be much more loosely defined and the sequence will be more fluid. Here you’re still doing discovery and reducing risk before committing to things.

And 6 months out you’ll have ideas of what you’ll build, but your evidence for these will be very light, so features here will be essentially unordered.

How this looks will obviously depend on your company stage, product org maturity and your particular domain, but the principle you’re working to is to remove as much risk up front as possible.

Recap

A product strategy explains where you will focus and why. It’s a coherent, high impact plan of action to help you achieve your objectives and deliver on your vision.

The best product strategies are evidence based, but no amount of discovery can make them completely risk free. It’s better to view your product strategy as a continual work in progress where you reduce the biggest risks up front, and learn as you go along. Articulating your strategy as a hypothesis as soon as possible highlights where the biggest risks are, and helps you focus your time on discovery. It also gives you something to show to others and get their feedback on.

Whilst creating a product strategy isn’t a purely linear process, there are 7 key components to consider that will help you pull together a robust plan:

Objective - defining what success looks like

Users - who you are building for and what do they need

Superpowers - where you can create value in a unique, hard-to-copy way

Vision - what the future you’re building looks like

Pillars - the main themes of work to go from where you are now to your vision

Impact - the value you’ll create by working on your pillars

Roadmap - the details of your plan and how you communicate them

Free templates

Product Strategy template [Notion | Google Docs | Word]

Jobs To Be Done - [Google Sheets]

7 Powers Cheat Sheet – [Google Sheets]

7 Powers Template – [Google Sheets]

Backlog - [Google Sheets | Excel | Notion]

OKR template - [Google Sheets | Excel | Notion]

Final words

Aakash here: I hope you enjoyed that guest post by Ed! I’ll aim to share more awesome content from guest creators like this from time-to-time. If you’re one of those creators, feel free to reach out to me.

Talk to you in a few days.

What a perfect guide. Thanks!

Terrific post✨👏