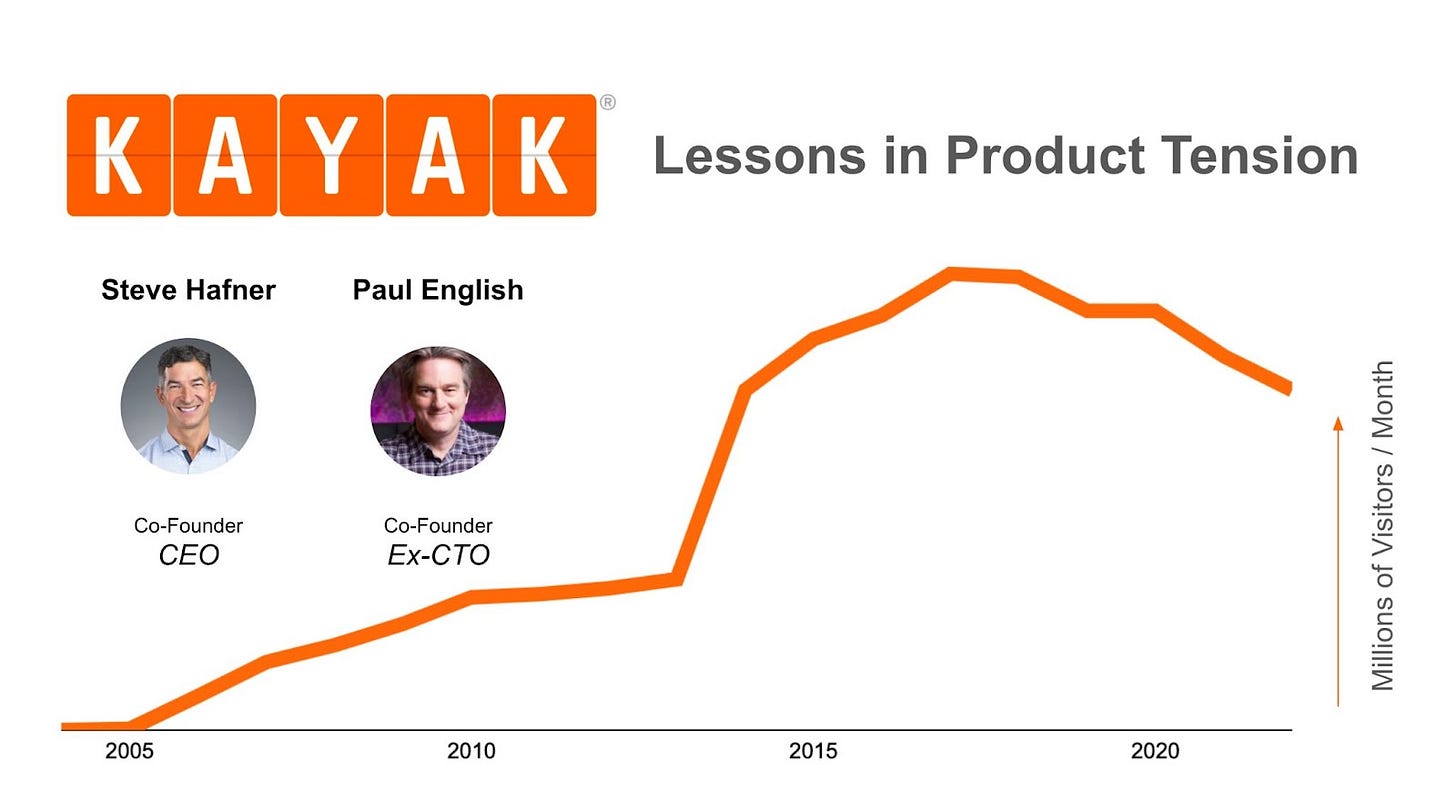

Kayak: Lessons in Product Tension

How does a company navigate the clashing waves of the travel industry? Adeptly, like a master using a Kayak. The meta-search engine started in 2004 can be a forgotten site in the business coverage of travel. Certainly, at 30M visitors per month, it’s not forgotten in the actual travel side of travel. Kayak is ubiquitous.

But, as a business, analysts and tech journalists rarely tend to cover it. Perhaps this is because it’s hidden inside Booking Holdings. Booking Holdings itself tends to be a bit of an unheralded company in tech. With a forward P/E ratio of 25x, it is one of the more tamely valued technology behemoths in the world today.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t a lot of interesting things going on at Kayak. From its ridiculously interesting founders - Steve Hafner and Paul English - to its constant product iterations, Kayak is a company for technologists and product people to pay attention to.

In fact, in Steve Hafner, Kayak has an Elon Musk-like multiple-time successful billionaire entrepreneur who still helms the CEO and product development leadership position at his company.

So, today, I am very excited to present a collaboration with Michelle Parsons, the Chief Product Officer at buzzy dating app Hinge. A few tours of duty ago, she worked as a product leader at Kayak. When Michelle and I were chatting about Kayak, the theme that kept coming up over and over was that of tension.

There’s the tension between what the executives want for the business and what the team can build. There’s the tension between what the product manager wants and what the designers & engineers want. There’s tension in every facet, and in every relationship, of the product development journey.

Because of Kayak’s unique position as a meta-search engine in the travel industry, it has particularly had to navigate tension throughout its life. From its inception to today, it has managed that beautifully.

Tension is something product practitioners feel day in, day out but is surprisingly not talked about much. So, Michelle and I are really excited to give a window into the life of managing tension adeptly, like a master Kayaker. Let’s start rowing.

Tension 1: People browsing but booking direct

In 2004, successful serial entrepreneur Paul English was looking for his next big project. Despite having a company, Boston Light Software, to Intuit, he had never managed to meet a Venture Capitalist. So, he set out to meet one.

That person would turn out to be Bill Kaiser at Greylock. Paul told the story on Masters of Scale:

I called Bill, and I said, "I want to start another company. And I want to do something really big." And Bill said, "There's an office at Greylock. Come set up tomorrow.”

Serendipity happens when you put yourself in the right places. One wintery evening as Paul was heading out from a meeting in Harvard Square, a partner told him that a co-founder of Orbitz named Steve Hafner wanted to create a travel company.

At the time, Orbitz was one of The Big Four travel sites, competing against Expedia, Priceline, and Travelocity for US customers. Clearly, Steve was a strong player in the industry. So, Paul took the meeting.

At Dinner, Paul got the pitch. The two shared a few Gin and Tonics, and Steve explained that the majority of people who used Orbitz did so to find a flight. But, once they did, they would book it directly on the airline and Orbitz would not get paid. It was a dramatic insight.

Indeed, this is the first lesson in tension from the story of Kayak. People browsing but booking directly created the opportunity for a new business. Instead of monetizing the booking, the company could monetize the traffic.

Paul and Steve began discussing a “pure search engine where we didn’t sell anything.” The idea was to aggregate inventory across The Big 4.

The chemistry was strong enough that Steve offered Paul the CTO position on the spot. It was a $150K, 4% equity job. Paul was interested in starting his own company, so he declined. But he did offer to connect Steve with someone in the group of 20 Boston CTOs that he ran.

Steve persisted: why didn’t Paul take the job? Paul said he could if it were 50/50. Steve agreed. History was made over dinner, and Kayak was born. The speed of its birth would carry out throughout its life.

Tension 2: Becoming a Thin UI Layer

That night, Paul would log onto Expedia. He knew immediately that a small team at Kayak could compete with the behemoth. The user experience was not up to snuff. It was cluttered and full of information.

Paul and Steve each put a million into the company. VCs put in an additional 5 million. With the capital in hand, the first calls Paul would make would be to his lifetime engineers. With the four of them on board, Kayak was ready to build its first version.

But, first, it needed to get content. Kayak would begin by just scraping content from the top four websites. It was “ask for forgiveness, not permission.”

In addition, in March 2005, the company struck up a deal with ITA Software for flight query results. This would also give the company a set of steady flight results to display to its users.

On Cinco de May, 2005, Kayak was released to friends and family. Then, in October 2005, it was released to the public. The site was simple, a contrast to Expedia:

As Paul said on How I Built This:

My friends at ITA used to say Kayak just sits on everyone else’s tech. It’s just a thin layer.

But that’s exactly what the Kayak team wanted. They could stay operationally efficient and have a small headcount, while making a big impact.

Others may not get the idea, which unveils the second lesson of product tension. User experience and a thin UI layer can be a product. But others may not realize that it is. That is not your problem, but your advantage.

Tension 3: Monetizing

Of course, the guys at ITA did have a bit of a point. Kayak had launched without any way to earn revenue. It was just a place to find flights, not book them.

The next big deal Kayak had to make was for revenue.

Steve called his former co-founder and Orbitz CEO, Jeffrey Katz. Steve worked out a deal with Jeffrey and the Orbitz traffic acquisition team to get paid per visitor they sent over to Orbitz. The price started at 50 cents.

This illustrates the power of having founders who are veterans in the industry. Perhaps no other person in the world could have worked out such a deal with one of the big four, when the company was still so nascent. But Steve did it.

Kayak became, “Search with us, book with Orbitz.” Kayak then leveraged the ‘book with Orbitz’ feature on Kayak in its Business Development (BD) calls with the airlines. They want something like this:

Kayak: We are selling American Airlines tickets on Kayak.

American Airlines: How?

Kayak: Through Orbitz. Don’t you want to get those bookings instead?

American Airlines: How much will it cost?

Okay, so it might not have been quite so easy, but the Orbitz booking trump card made it relatively easy for Kayak to get most airlines to pay them directly over the next couple of years.

Another important deal the company would strike was with Google, the leading search platform. This would provide the company with sponsored link advertising inventory to generate revenue.

Between Orbitz, the airlines directly, and Google ads, Kayak created three diverse revenue streams out of a thin UI layer. The only rub was, the same people paying the ads were competing for the same traffic.

Tension 4: Competing with OTAs for Traffic, but selling them ad placements

Kayak became this wonderful “fine line” business. It had to work the fine line of competing with the Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) for traffic, but then selling them ads. To draw a distinction, Kayak established itself firmly at the top of the funnel. It did not actually facilitate transactions. It was the “Google of Travel.”

OTAs like Orbitz, Expedia, Booking.com, and Priceline, take a cut of 15-20% of hotel booking fees. But metasearch engines like Kayak and Google Flights direct the user to a third-party OTA or direct source.

This would enable Kayak to develop hundreds more relationships with travel suppliers and OTAs, in addition to Google and ITA.

Over the first five years of Kayak’s life, it was able to establish over 300 of these relationships. This generated a great flywheel: additional content generated better search query results, which generated more traffic, which enhanced the search query results.

By 2007, Kayak had become the eighth biggest travel site, with nearly 6M monthly visitors.

Tension 5: Different acquisition and monetization features

But competition in the space was fierce. Kayak was a meta-search leader on the flight side. But on the hotel side, there was room for growth. Hotels were not only a more lucrative business, but also the next logical choice for travelers to make after booking their flights. In hotels, the OTAs and a meta-search player Sidestep dominated.

As a result, in December, 2007, Kayak raised $196M and used the funds to acquire Sidestep. This would begin a three-year process of integrating Sidestep’s hotel user base, results, and experience. Over time, Kayak would quickly scale quickly into the hotel side of travel. This gave Kayak a critical new way to monetize its already loyal flight users.

In the meantime, Kayak continued working for speed on the product development front. In March 2009 Kayak debuted its mobile app. It was considered the first true mobile travel app. Kayak was able to capture significant shares of users browsing the app stores for travel options, regularly atop the search rankings and getting featured on the homepage.

In April 2009, Kayak signed a 5 year agreement with Orbitz for Kayak to have full access to Orbitz’s travel content, in exchange for Orbitz exclusivity in some of Kayak’s search results. All the pieces were in place for a strong business for years to come.

As a result, just five years after commercial launch, the company filed its S-1 in November 2010. Kayak was making $140M in revenue with just 140 employees. It had wonderfully walked the line of tension with its partners.

But, that wasn’t enough for a hesitant tech market. The company would face a 2-year delay to IPO. Market conditions for tech IPOs were not hot.

Then, in 2011, Google acquired ITA Software and rebranded its offering to Google Flights. Although Google maintained the availability of results to Kayak, at the time this was viewed as another risk to Kayak’s market share (which turned out to be true). ITA provided 40% of Kayak’s air search results, which accounted for 85% of search volume.

Conditions continued to worsen for Kayak. Google launched without ads in September 2011. For many, the product was considered another leap forward in the travel industry from a UX design perspective, just as Kayak was a few years earlier.

But UX was the company’s first moat. It wasn’t going to sit idly by. In response, in January, 2012 Kayak launched its own redesigned app across platforms:

Beyond adding a darker veneer to the site with considerably more white space in the results, the redesign had three important feature changes:

It added a greater prominence of options beyond flight to better monetize its existing user base in the header. This doubled down on the success of the Sidestep acquisition.

It added a display banner ad slot and three logo slots for OTAs to the top of the right nav, to create more ad slots to monetize.

It added a compare site feature to create differentiation for its meta-search offering. Kayak’s results were a superset of those offerings.

In the same quarter, Kayak also Launched direct booking for flights, starting with Air Canada. Instead of being redirected to book through the provider, Kayak would facilitate bookings making for a more seamless user experience. With all these changes, in Q1 of 2012, Kayak achieved positive net income. It was finally ready to go public.

On July 20th, 2012, Kayak became a public company. By the time Kayak IPO’d, the company had a whopping 53% share of the meta-search market. Things were going extremely well.

Things were going so well that, mere months after its IPO, in November 2012, Kayak was acquired by Priceline. At the time, the $1.8B deal was Priceline’s biggest. Half of the company’s employees became millionaires the day Priceline bought Kayak, and bottles of champagne were popped. Those who kept their shares, like CEO and founder Steve Hafner, have benefitted tremendously (it is now called Booking.com due to the success of that property) with a 3.4x in value since:

Tension 6: User needs & business metrics

As an arm within the larger Priceline and Booking.com behemoth, things changed dramatically for Kayak. For one, Paul English began making plans to leave as early as February 2013 before the sale was final. By January 2014, Paul had stepped down from CTO and moved onto his next venture.

But, in terms of the business, the goals also changed slightly. Kayak was no longer just a thin UI layer: it was part of a larger OTA business. The goal for Kayak was not simply to grow itself, but to play nice with its corporate partners, as well.

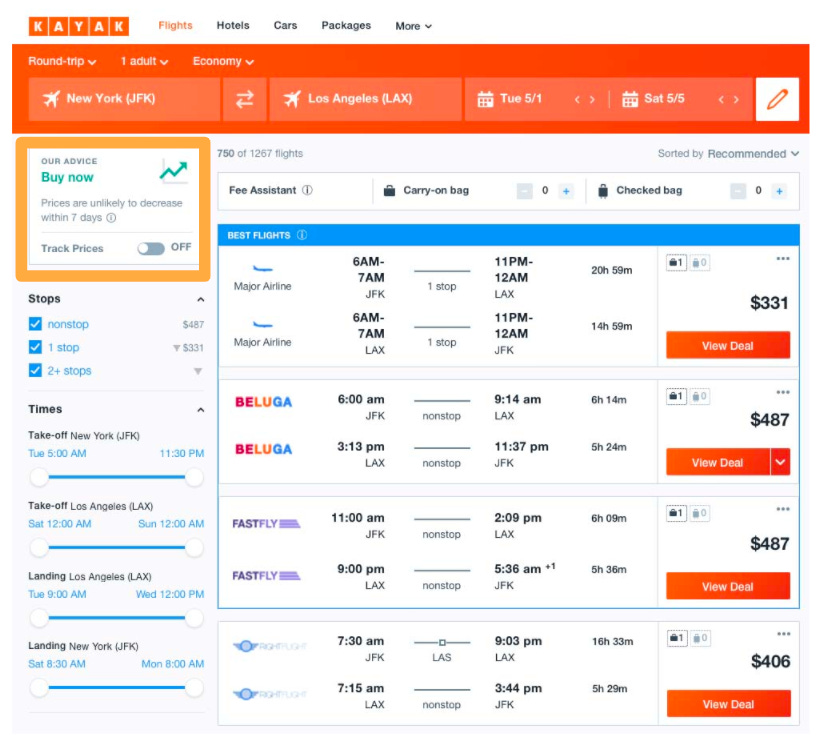

Ever the product innovators, a big feature launch for Kayak was to add its price forecast tool. Quickly, it became synonymous with the value props of the site:

It was a feature that stuck. Kayak could use its proprietary search data to give users unique information. Users loved it. It helped the user and the business metrics.

Not every feature was like that. One of the features Kayak built while I (Michelle) was there that did not stick was in-page hotel upsell. The feature helped the user book the additional parts of their trip before confirming the flight. Presumably this helped the trip planner save time, but it added more information and decision points that the user had to incorporate into their final purchase decision. The problem with the feature is another lesson in tension: it solved a user need but not a business one.

The business metrics at Kayak necessitated that users convert quickly. While upsell was a useful feature for the long-term user needs, it slowed down conversion rates. Slower conversion rates hurt Kayak’s performance impacting revenue. So, it did not roll out the feature.

Tensions 7: Conversion Goldilocks

Kayak was at the time highly reliant on paid search. In paid search traffic, you bid per click. Google sends users to places where they convert well. But, as I (Michelle) learned, the business can be hurt if you convert too well.

Another set of features the team built was around improving conversion rates on hotel results. The team had done some deep user discovery and found that the job to be done for most users was to evaluate between 5-6 hotels, which were the top options that met their criteria (price, location, amenities).

So, the team worked on the enhanced hotel results page. The goal of the feature was to help a user learn more about the hotel (think: amenities, neighborhood, dozens of photos, room details, etc.) to more easily evaluate and purchase a hotel stay directly on Kayak. Conversions increased exponentially.

However, the conversion rates were so high that they hurt the clicks and acquisition volume Kayak received from the providers it linked out to. Users weren’t browsing multiple providers to find this information anymore since Kayak was doing it so well. So Kayak received lower revenue per visitor. As meta-search is a thin UI layer, for its conversion “goldilocks,” the team went too high.

As a result, the team had to build a page that balanced clicks and conversion. What this meant practically for Kayak’s hotel results is that the page does not have every piece of information to lead to instant conversion. It is balancing converting you quickly to rank well on Google Search but also enough left open to encourage you to visit sites Kayak links out to.

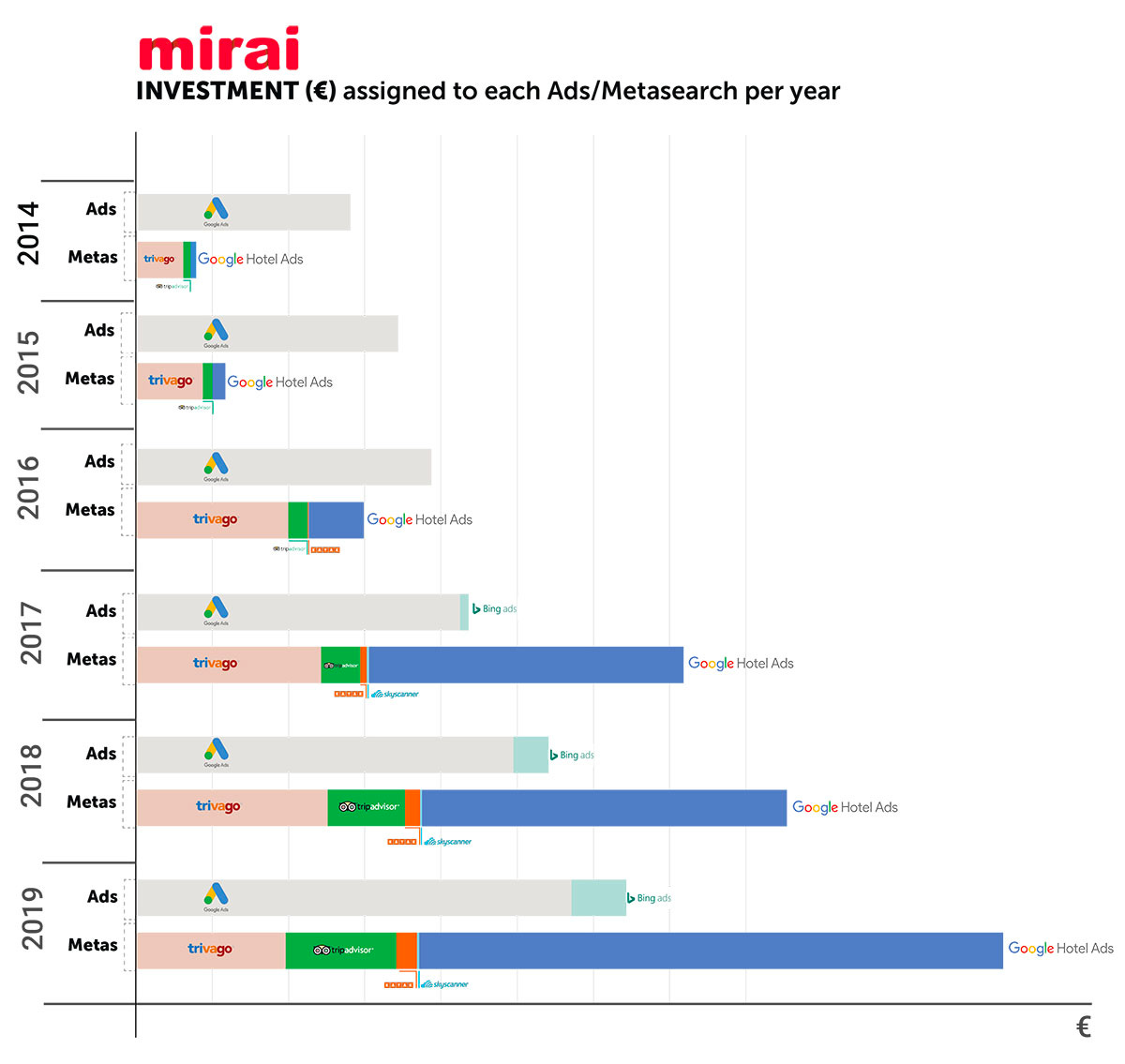

From 2014 to 2019, Kayak’s strategy worked and it grew. But not nearly as fast as Google’s own travel search. Indeed, a research report by Mirai found that Google had grown to become bigger than the rest of the metasearch market through its hotel ads by 2019.

Tension 8: Becoming a 1-Stop Shop

In the American travel market especially, Google was the top dog. To reflect the appropriate stature of Booking.com, Priceline’s European unit, in 2018 the company renamed itself Booking.com (Ticker went from PCLN to BKNG).

Meanwhile, on the metasearch side, Kayak was not just fighting Google. Kayak also had to contend with the rise of Airbnb. Unlike the major airlines or hotels, Airbnb was not going to provide its results to a metasearch engine like Kayak, let alone pay for traffic from it.

To truly be a “1-stop shop,” for its customer’s needs, Kayak needed to pull in vacation rental properties. Luckily, as part of Booking.com, Kayak had access to one of the largest inventories of vacation rental listings. However, the final lesson in tension is: how do you add more information to an already successful business?

In the case of Kayak, as the chart from Mirai shows, it did grow its hotel business substantially, even if it was smaller than Google’s. So the team needed to think about how they could expand their accommodation offering to compete not only with hotel providers, like Google but also with alternative stay providers like Airbnb. Vacation rental stays were still in their infancy and weren’t widely understood or trusted across the general population. A key question emerged: How should we integrate and display vacation rental listings on Kayak, should we integrate vacation rentals into hotels or split them out in their own UI? Each came with its own set of opportunities and challenges.

As the team investigated the user needs, users were open to seeing accommodations of any type - but judged the amenities of vacation rentals and hotels to be different. So, the team made the bold move to integrate vacation rental properties directly into its hotel search results page. After 5 hotels, a relevant vacation rental result would appear with unique details that clearly differentiated it from hotel results.

To navigate the tension of making it clear to the user, the team built a differentiated toggle at the top of the results page allowing users to filter out the content if they so pleased. So if a user was searching for hotels, they saw a clear indication that the results set contained multiple types of properties helping educate users while giving them options to fully control their experience.

While these were only the first additions in the quest to become a 1 stop shop for users, Kayak balanced user understanding and openness to this new type of experience with business goals.

Present

Since integrating vacation rentals, it has been a wild ride for Kayak. Covid hit the entire travel industry hard, including Kayak. The company had to cut 25% of its headcount at the start of 2020.

But, it fought back. As a product-first company, Kayak pivoted to adapt to the new environment. Kayak launched a Covid-19 resource, which showed where users could go to get refunds for canceled travel, as well as illuminated specific covid travel restrictions as things started to open back up across the globe.

The company also innovated on its marketing. In airports, it built a hilarious safe sex ad with masks:

With that spirit of innovation across product, marketing, and the whole company, Kayak was actually able to rehire half of the people that it had to let go.

It also moved into physical spaces for hotels in order to better own the end to end travel experience. In April 2021, Kayak launched a new hotel chain. Its first location in Miami Beach is an ultra-luxury boutique.

Future

That move, as Steve explained in an interview, has also coincided with Kayak attempting to make more moves into the overall hotel tech stack. Kayak is not going to be just a consumer company for long.

A true innovator at heart, Steve still has big dreams for Kayak. We expect him to reach them.

Takeaways

The story of Kayak is a story of tension, one that the early team managed in choppy waters quite unlike the ones of today. Nevertheless, the company has succeeded and thrived.

It’s one of the rare examples of a technology business to live on successfully after acquisition. It has managed to exploit the initial product tension of its founding - people browsing but booking direct - for nearly 20 years now.

Although it is not quite the thin UI layer it began as, it still faces tensions in monetization and competing with those it sends traffic to. With the ongoing race to the bottom with travel affiliate fees, it also faces ongoing headwinds for its revenue. The user needs and business needs do not always align, but the company has maintained conversion goldilocks to become a true 1-stop shop for consumer travel.