How not to be a PM: Lessons from Elon

+ How to show a path to profitability

In Today’s newsletter:

How NOT to be a PM: Lessons from Elon

How to show a “Path to Profitability”: Hims & Hers Case Study

Marc Lasry’s 5.36x Return in 9 years: How he did it

The Biggest Problem in Recruiting

But first — I’m excited to share today’s newsletter sponsor: Round. Round is a private network of leaders who want to maximize their impact in tech, and on the world. Founded by serial entrepreneurs, Round counts senior executives from Amazon, Canva, Flexport, Roblox, Zapier (and basically any innovative tech company you can think of) among its members.

The Round experience supports leaders who are building the best tech through curated private events, access to industry leaders, and a community of talented peers. Ready to join? Mention Product Growth to skip the waitlist.

How NOT to be a PM: Lessons from Elon

Elon’s Twitter takeover has been a masterclass on how NOT to PM. 6 lessons from Elon of what not to do:

1. Prioritize by user likes

Elon tweeted for feature suggestions and said he would prioritize by most likes and least work. This is also a common product strategy: build what the users ask for.

The problem is that users don’t know what’s best for the business. In the Venn diagram of business and user value, the best product features sit at the intersection.

Users don’t know what those features are. You have to invent on their behalf. Start with a deep understanding of their needs, layer on what’s only recently possible, then ship.

2. Pursue exec pet projects

The Twitter blue premium subscription has 300K payers. That’s just $29M yearly revenue in a multi-billion dollar business. It’s meaningless.

And it would have been completely predictable if they analytically sized the project and did user testing. But instead of doing rigorous sizing or user testing to validate, Elon just went with his pet project.

This is a common tendency of junior PMs as well: please the VP. It’s a mistake. The extra cycles to do dig into features with data & user research are worth the squeeze.

3. Set aspirational dates to ship

Elon chronically sets dates that the team misses by weeks or months (or years in the case of Tesla). For instance, the team rushed to ship Twitter Blue to hit his deadline.

But the rollout was a disaster, and they had to roll it back. People were impersonating companies and swinging stock prices. The final product didn’t come out ‘till months later.

Setting crazy dates stresses teams out and results in botched launches. Realistic timelines allow teams to ship quality features and maintain their sanity.

4. Ignore the revenue driver

The NYT reported Twitter advertising revenue is down from $5B/year to $3B. That’s an enormous 40% dip.

Elon ignored the core business of advertising. He fired the sales staff that maintained and grew relationships. Then, he offended many advertisers - prompting them to leave the platform.

That was exactly the wrong strategy. Great product work would have improved and nurtured the ad business first. A 1% improvement on 5 billion could have generated $50M - more than Twitter Blue.

5. Launch without experiments

Elon changed the default feed people look at from the algorithmic ‘for you’ feed to the ‘following’ feed. But the ‘following’ feed is full of retweets and doesn’t encourage discovery of new authors.

It could be a worse experience. But, because Elon didn’t ship the change as an experiment, he’ll never know.

Doing things blindly is worse than doing nothing at all. Shipping major changes that could easily get to stat sig in a few days to everyone is just lazy product work. Prefer the scientific method.

6. Fire the SMEs

The product and subject matter expert (SME) teams at Twitter have been decimated. These are the experts who could have spoken up to avoid the above 5 mistakes. Heterogeneity of thinking is a wonderful thing. Elon firing non-loyalists has removed all of that.

So, now he’s on the treadmill of bad decisions. The people that are left don’t speak up. He’s surrounded by a bunch of people confirming his opinions. That’s the easiest recipe for product failures. Debate with SMEs hardens the best roadmaps to diamonds.

So there you have it, 6 lessons from Elon on how NOT to PM.

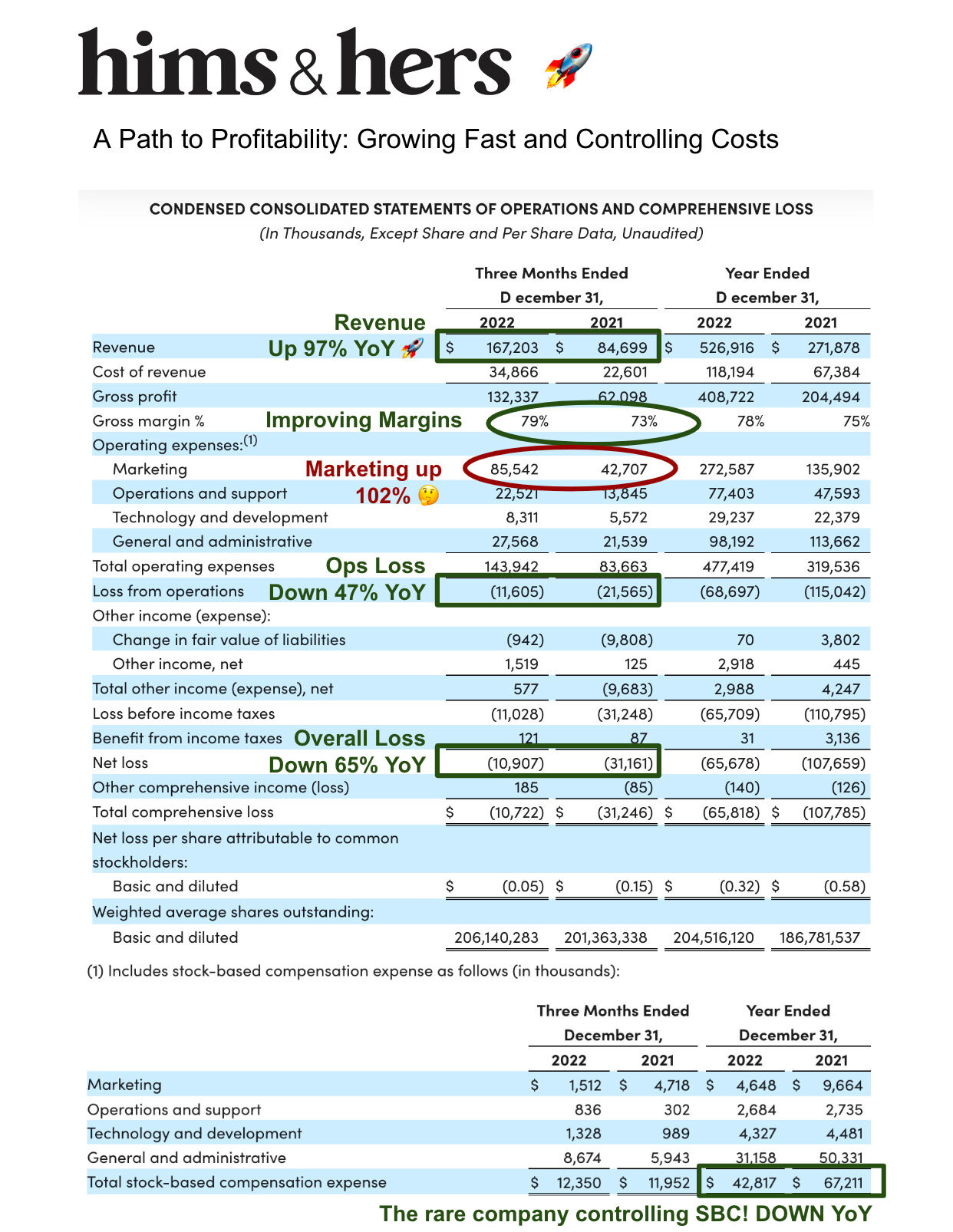

How to show a “Path to Profitability”: Hims & Hers

"A path to profitability." It's what investors are demanding in this climate. hims & hers is actually doing it:

hims & hers operates in telehealth. It gets people video chat doctor's appointments for stuff they may not otherwise want to talk to a doc in person about, eg:

Erectile Dysfunction

Hair Loss

Mental Health

Then it gets them subscriptions. It's shown 5 main drivers on its path to profits:

Driver 1: Subscriptions are growing nicely

Growing subscribers is the number one engine of its growth story. They are up 87% year over year. It continues to grow them via marketing (up 102% yoy). It's also grown rev / sub 10%.

Driver 2: It's kept a lid on costs

Many of the other 2021 newly public companies have seen ballooning stock-based comp and other operating costs. hims & hers hasn't. SBC was actually down yoy. That's far different from other 2021 market entrants.

Driver 3: The company is showing leverage

Revenue was up 97% but operating costs were only up 72%. For every operating dollar spent, it's able to generate more revenue than last year. This fundamental operating leverage is driving the company toward profitability as it scales

Driver 4: The economics for these products is quite nice

Many of the drugs hims & hers sales are generics. These are proven products, like Viagra, that work. But it's able to produce them without R&D. Gross margin of 79% enables the company to re-invest in marketing.

Driver 5: It's building for a specific audience

hims & hers is a smaller niche player in telehealth. It's building for millennials and city-folk who like its simple, modern branding. By staying true to its core, it's able to eat away share from the leader, Teladoc.

Marc Lasry’s 5.36x Return in 9 years: How he did it

In 2014, Marc Lasry bought the Milwaukee Bucks for $550M. This week, he sold them for $3.5B.

That’s a cool 5.36x return. How’d he do it?

1. Buying cheap

Any way you cut it, Marc found himself a deal. The same month he bought the Bucks for half a billion, Steve Ballmer paid $2B for the Clippers. But the Clippers went 57-25. They were winners. Marc bought losers. The Bucks had just gone 15-67 for the season.

See, buying a winner is expensive. Instead, Marc bought a team with potential. The Bucks had Giannis Antetokounmpo at the time. But he had only averaged 12.7 points. Marc saw opportunity in “the Greek Freak.” And he capitalized:

2. Investing to become a winner

Marc hasn’t been cheap with the Bucks. He’s paying a $70M luxury tax bill this year. Last year he paid $50M. That’s all extra investment into the team. Totally optional.

And the investments have paid off. Giannis was the MVP of the NBA in 2019 and 2020. And the Bucks won the championship in 2021. Marc turned a losing franchise into a winner. It’s been a classic turnaround.

3. Selling at a good time

Marc put the cherry on top of the deal by selling when the market was high. Sports franchise valuations are going bonkers. The Walton family’s purchase of $4.65B for the Broncos set a new bar late last year.

But that was the NFL. Surely, no one would pay so much in the NBA? Then, Matt Ishiba bought the Suns for $4B last month. He showed it could happen in the NBA, too. Marc saw the high watermark - and sold.

As a billionaire Private Equity investor, Marc ran his playbook:

Buy cheap

Improve the asset

Sell high

It’s been great to observe.

The Biggest Problem in Recruiting

The biggest problem I see in recruiting: Writing assignments in interview processes where you ghost the candidate afterwards.

If you asked the candidate for many hours of free work, at the very least have a call for feedback after.

I think a much better strategy is to ask for a writing sample of something they have written. This way, you get to assess their writing, and they get to be efficient with their time.

An alternative strategy is to pay candidates for the time spent writing at a reasonable rate.

Asking for free work as a filtering process is bad form. If they put in an investment, you should put in an investment back.