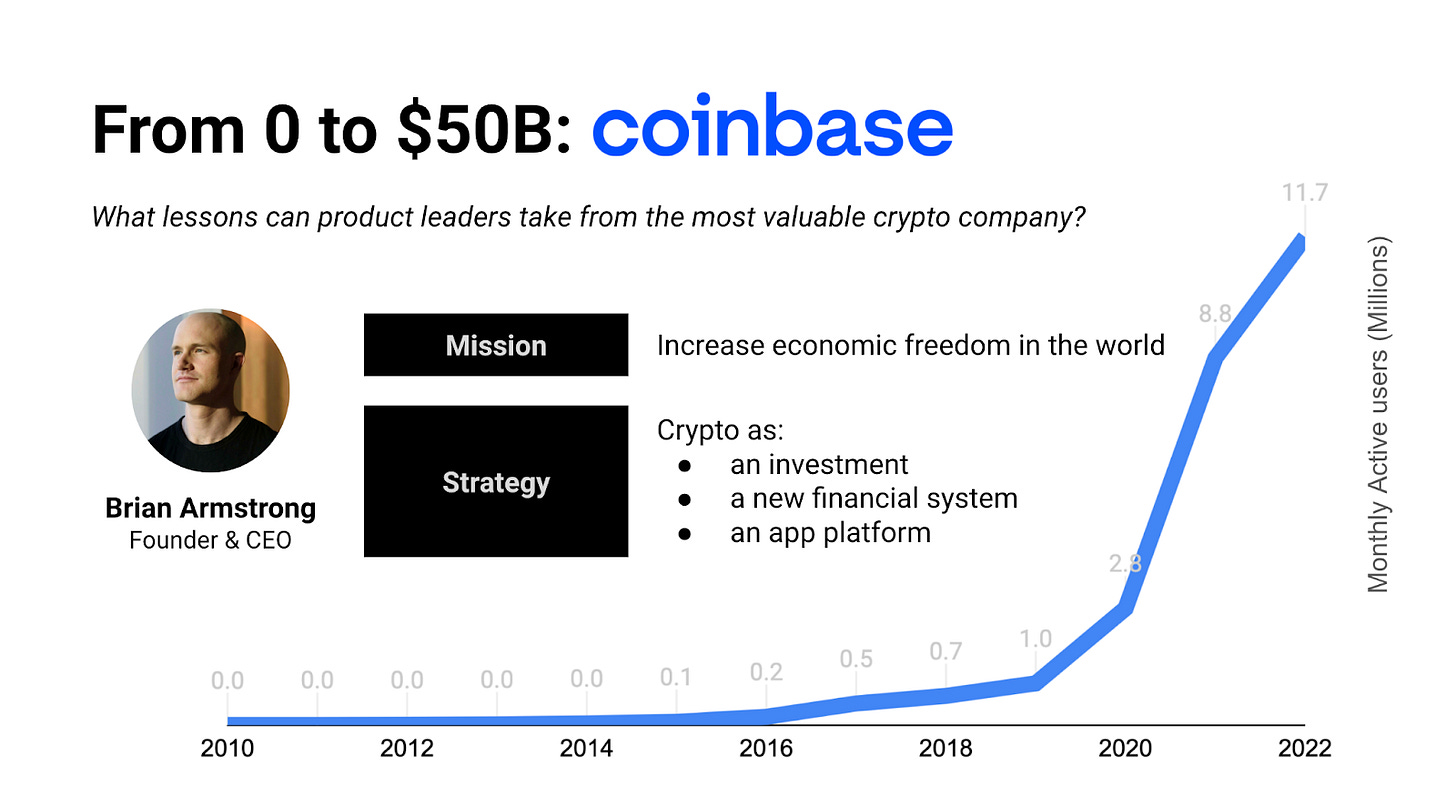

From 0 to $50B: the Coinbase Profile

5,000 words at the intersection of web3, fintech, and product growth

Brian Armstrong just bought one of the most expensive homes in the state of California. For $133M, his modern Bel Air mansion is now one of the priciest single-family home transactions ever.

The self-confessed “on the spectrum” (of Autism) CEO has managed to become one of the world’s richest entrepreneurs, as well as one of the most powerful men in web3. With the purchase of his Bel Air mansion, Brian has coronated his position as one of the richest and powerful men in the world, period.

With that position, both Brian and Coinbase have been the subject of several amazing profiles. Wired, The Generalist, Inc Magazine - it seems like everyone has written about Coinbase.

So, we’re not going to cover the things you’ve already read everywhere. Instead, today I want to focus on: what lessons can product builders take from Coinbase? Like we did for PayPal, Stripe, Nubank, and PayTM, we want to break down the new FinTech giant, so we can replicate some of the learnings at our workplaces.

The twist with Coinbase is that it is one of the most interesting companies in the crypto and blockchain worlds. One of the ongoing strands we are exploring in Product Growth is how to build for web3 specifically. Every PM is being asked to evaluate the impact of web3 on their business.

This makes Coinbase one of the most interesting companies to explore. It is the highest public market cap pure-play at $50B, but it also is a very centralized exchange. Unlike Uniswap, for instance, its decentralized alternative, there is still an element of trust in the centralized player. Many PMs will also need to take a centralized entry into the web3 world.

I’ve been closely following Coinbase since Kevin Rose’s interview with Brian in 2013. I have been using the product since 2016. My research note for Coinbase had 150 articles when I started this piece. After that base, to write this piece, I combed through every post on the Coinbase blog. I watched YouTube videos and read Twitter threads. All in all, this piece took well over 40 hours. That’s a whole work week of value for free.

You’ll notice my first-hand research leads to several different interpretations of history. So, strap in as we explore 10 product lessons from the growth of Coinbase.

2010

Lesson 1: It’s Easy to Be Skeptical About the Future

What were you doing on Christmas Day in 2010? I was sleeping in and overeating.

Brian Armstrong wasn’t. As a fraud systems engineer at Airbnb, Brian was reading cypherpunk literature. It was then that he came across Satoshi Nakomoto’s Bitcoin whitepaper. Released two years prior, Bitcoin was already a toddler by that time.

Plenty of smart people were skeptical of Bitcoin then. Plenty of smart people are still skeptical about Bitcoin now. But, Brian was built differently. Brian was an engineer looking for a startup to build.

Having grown up in San Jose, California, at a “brutal” high school where he “got made fun of pretty hardcore,” Brian had the backbone to withstand the criticism and stay a hungry nerd. He found his tribe, eventually. As a high schooler, he and his friends tried new companies every six months.

That backbone would prove useful. It helped Brian to stay contrarian. So, when he read the Bitcoin whitepaper, he knew he was on to something. His mom told him he should probably come downstairs to spend time with the relatives out of town.

As Patrick Collison of Stripe points out, “Pessimists sound smart. Optimists make money.” Instead of being the smart skeptic, Brian was the optimist.

Lesson 2: Get Out There and Talk to Users to Understand Opportunities

Brian was a man possessed for the next weeks and months. He kept re-reading the paper. The trust problem, and the importance of decentralization kept seeming more obvious the more he read it.

He was worried he was actually too late to the whole thing:

It’s funny because I actually remember feeling like I was late to the game…. So actually the first thing I did was kind of trying to talk myself out of doing something in Bitcoin.

At the time, over 70% of all Bitcoin transactions were being handled by the exchange Mt. Gox. It felt like the world of NFTs and OpenSea, with its dominant market share scaring off competitors, today. Could anyone really compete?

2011

But Brian persisted. He went to a couple of Bitcoin meetups in 2011. There were the types of affairs with 10 attendees. 90% of people see the size of the crowd and turn around, to the more comfortable surrounds of their known friend group at the bar next door. But not Brian. He kept going, meeting the community, and learning their pain points.

Actually going out and doing that crucial user discovery work helped Brian have the insight that the main Bitcoin client was the only way to interact with Bitcoin. But the client was desktop only.

There was no Bitcoin wallet on the internet. There were a few things like a javascript library, but, generally, using and interacting with Bitcoin was both highly technical and difficult.

Lesson 3: Rapidly Release an MVP

So, Brian and a friend experimented with an open-source Android wallet. It was a quick open-source throwaway project. They released it without any marketing. It received a ton of traction: 15K downloads in two weeks, HackerNews #1, a Wired writeup. It’s fair to say things went much better than the duo had originally thought they might.

Because all the data was stored on the phone, Brian and his friend weren’t taking any risk with people’s personal data. So it wasn’t a complete solution. If something went wrong and the data was corrupted on the phone, the bitcoins were lost. The choice was intentional: they didn’t want to create a real company storing people’s data, because they both had full-time jobs.

However, the traction was signal enough that they should work on the complete solution. The idea was validated that people were really interested in Bitcoin, and if it became easier to use, people would flock to that solution. As Brian describes it:

The day we released it, I realized that somebody is going to have to make a really rock-solid cloud service for this. The future is going to be a thin client. While the blockchain was 300MB then, it was growing exponentially.

2012

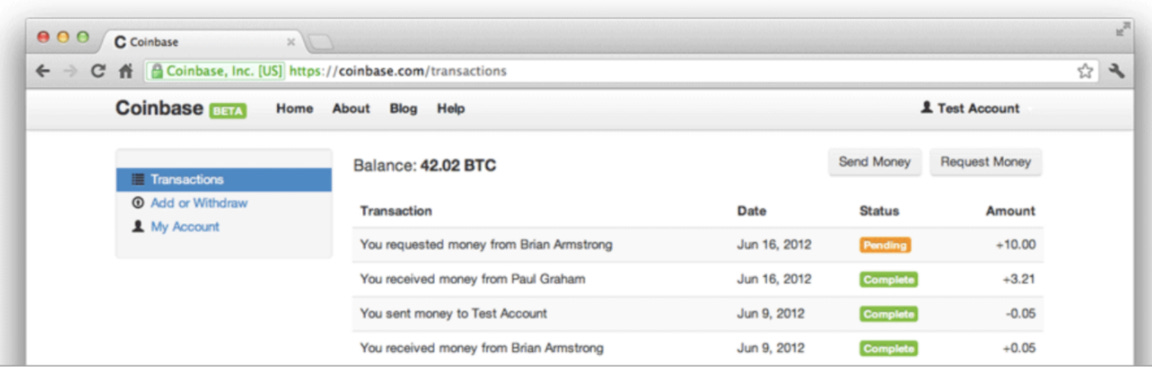

With the proof in the pudding from the open-source throwaway project, Brian was almost ready to work on Coinbase full-time. Before fully making the leap, he used nights and weekends to build bitcoin products. One of Brian’s early insights was it had to be dead simple to send and receive Bitcoin, if it were to be used for payments.

He had cold-emailed YC partner Garry Tan about how to find a co-founder. Since Garry replied, Brian followed up by sending Garry Tan 0.05 BTC (today worth $2.1K) over email.

It was a remarkable example of a single engineer building fast. From there, Brian teamed up with the founder of Blockchain.info, Ben Reeves, to build a fully functional online wallet prototype. The two worked out kinks in the security and shipped it.

With the prototype in hand - though not launched - Brian was ready to apply to Y Combinator (YC). The Coinbase website and blog were set up.

Even at the time, competition to get into YC was fierce. The duo pitched themselves as having the radical idea that anyone, anywhere, should be able to easily and securely send and receive Bitcoin. As a result of the engineering work and clever pitching, Brian and Ben were accepted.

Getting into Y Combinator would be the validation needed for Brian to make the leap. In June 2012, Brian left his cushy Airbnb gig to work on things full time. Coinbase was born.

A day before YC began, Brian decided that he and Ben did not work well together. With a quick email, the duo became one.

Brian would make it through YC as one of the few solo founders. During YC, Brian soft-launched the product, signed up 15,000 people, and crushed Demo Day. This led to a $600K seed round to round out 2012.

Amazingly, Brian did all of the work in the second half of 2012, more or less, on his own. In addition to the consumer user interface, Coinbase released an API by September.

Lesson 4: Iterate to Make the Tech More Accessible

Brian would work days, nights, weekends, and vacations. Midday December 31st, he wrote “Sending Bitcoin to People You Know With Ease,” on the Coinbase blog. Brian was solving problems in the user experience of Bitcoin.

This time, it was about those pesky wallet addresses. Anyone who has used crypto knows the feeling: you have to triple check a 30+ character address. You don’t want to send the money somewhere you are not getting it back. As he said:

One of the more difficult things about bitcoin for the common user is dealing with the 30+ character addresses that are referenced to send or receive money. Rarely would one want to see these addresses — it’s much easier and more intuitive to refer to someone by their email address.

It was a genius solution, one precipitated by Brian’s work earlier in the year on Bitbank. The easy onramp would further the growth of Coinbase.

Of course, working alone would not be sustainable forever. By the end of the year, Brian would find his co-founder: Fred Ehrasm. A former Goldman Sachs trader, Fred would prove integral to Coinbase’s early success.

2013

Another important team member at the time was a security engineer in Germany who Brian met on Github. A contractor, he was an engineering savant and able to validate all the security holes and edge cases needed to operate an online wallet.

Together with the contractor, the team released several security features. A popular one was allowing you to export your bitcoin to a paper wallet. A paper wallet allows you to store your cryptocurrency offline. It is the dominant method still used to this day for large holders.

In addition, the team made the decision to keep the vast majority of customer funds offline. Instead of pushing security to the user, where if someone got your password all your money could be gone, the company took a more active responsibility. Brian was already thinking like a banker:

If you were to go to somebody like my mother say, “well, here’s your online banking, and, by the way, if you forget your password, all your money’s gone in your bank account,” that’s not really a good way to build a relationship with a mass-market audience.

This insight would be critical, and the foundation of the company’s future success. Brian identified that what was missing in the Bitcoin ecosystem was a mass-market, easy-to-use product. And, a big part of such a product is security. So Coinbase provided security-as-a-service to customers, instead of pushing the responsibility onto them.

The team takes the vast majority of customer funds offline, then does key-splitting into various parts. Those keys are then distributed all around the world geographically. Then, to actually use the keys, two need to turn at the same time. So, it creates redundancy where you need to hack two sets of keys. In addition, there is redundancy in the key splits so there is no system failure of one key split is lost.

The remaining funds are left in a so-called “hot wallet” so that users can take their crypto in and out of fiat currencies like US dollars. It’s usually around 5% of the total funds, but as volatility increases, the amount automatically increases to accommodate additional user activity.

In addition to security features themselves, Coinbase also built a massive test suite. Brian remained paranoid about people trying to attack the online wallet. By the end of 2013, the Coinbase engineering team had a suite of over 200 tests running.

Many people are puzzled by how Robinhood, for instance, can offer commission-free Bitcoin trades, while Coinbase charges 1%. This security combined with access is what customers are paying for.

Robinhood has had crypto for years but still does not actually make the currency available to users. So if you buy Ethereum on Robinhood, you can’t use it to buy an NFT on OpenSea. It is just an investment.

At Coinbase, the currency is actually yours, you can take it out and use it. Users are hiring Coinbase for the job-to-be-done of secure Bitcoin access and storage.

In addition to security-as-a-service, in November of 2013, Coinbase began insuring people’s deposits. The company worked with Aon, the world’s largest insurance broker, to cover losses due to breaches in physical security, cyber security, accidental loss, or employee theft. Although it did not cover crypto loss if a user was negligent in maintaining their private keys, but it was a huge step up from other exchanges.

This was very different from the Mt. Gox model. While Mt. Gox was trying to be the New York Stock Exchange and Fidelity, Coinbase was only trying to be Fidelity. It wasn’t trying to make any money on the spread. It was just sourcing for users. And then providing them security, and peace of mind, that those assets would not be hacked.

This set up Coinbase to focus on a different persona than most other platforms. Instead of focusing on the retail trader, Coinbase focused on developing more of a professional trader tool and B2B service. By addressing security and insurance, it made the product more palatable for those types of users.

The team’s wise decisions would lead Coinbase to dramatic growth over the course of 2013. At the start of the year, transaction volume was in the $15M a month range. By the end of the year, it was two orders of magnitude higher than that. Coinbase was amongst the hottest companies in the Bitcoin space. Along the way, it bagged a $6M Series A and $25M Series B.

There’s a lot more to the story - but it was too long for email: