📱 The World's Most Valuable Per Employee Company: Supercell

Remaking Gaming With 340 Employees

When it comes to legendary cultures, and small teams redefining industries, Supercell is a shining example. Last week, The Information reported Tencent is in talks to buy out the remaining 16% of external investors in the Finnish gaming super company. In the process, it plans to mark up Supercell’s value to $11B.

Supercell only employs 340 people. It has achieved a valuation of $32M per employee. You would be hard pressed to find a company in any sector anywhere in the world with a higher valuation per employee. Common examples when I searched and asked around include Shopify, $6M per employee as of publishing, and Apple, $18M per employee. Supercell blows them out of the water.

It is also higher than any comparable gaming companies in that valuation range. The closest is another European gaming company, Modern Times Group out of Sweden, at $10M per employee. The well-known American gaming companies are far behind: Activision at $5M, EA and Zynga at $3M. Supercell has created value per employee unlike any company in the world.

It continues to make shrewd moves to earn that valuation. Most recently, it sponsored Mr Beast’s real-life Squid Game YouTube video. The show was the most watched ever on Netflix. And, like the hit show, Mr Beast’s video had 456 people duke it out for a big cash prize. Of course, unlike the show, this time the games were not deadly.

The video was one of 2021’s breakout videos on YouTube. It broke almost every record in YouTube’s books. Among them: it was the fastest non-music video to surpass over 100 million views, a feat it pulled off in less than 4 days. As of publishing, 4 week later, the video has over 175M views. The Netflix show has had 142M viewers. So Mr Beast’s YouTube video has had more reach than the hit Netflix show. That is mind blowing.

As one of the most popular YouTube videos of all time, Mr Beast’s video can be expected to achieve many more milestones over its life. And, forever, Supercell’s Brawl Stars will be branded at the center of its prize pool. It was a huge moment for the game.

And it is a huge win for Supercell as a company. In the first week after the video was released, first time downloads of Brawl Stars saw a 4.5x surge week over week following the video. For a game that already has $1.4B in lifetime revenue, the new players will be a reinvigoration for the player base and developers alike.

Plus, Mr Beast’s video is likely to be the gift that keeps on giving. It is expected that the video has a long tail of views over its life. It would not surprise me if the video eventually surpasses 1 billion views.

As a result of Supercell’s shrewd move, along with many other things, Tencent is making the move to buy out other investors. But the $11B valuation is not all good news. The company had reached an implied valuation of $10B all the way back in 2016, when the first part of Tencent’s transaction to acquire 84% of the company happened.

Since then, yearly revenue at Supercell has actually decreased. That is remarkably mediocre performance, especially considering nearly every gaming company saw a gigantic bump in the Covid-lockdown year of 2020. So, what is the Supercell story? Let’s explore together:

How did it rise to be a Decacorn in just 6 years?

What happened to flatline it in the ensuing 5 years?

Can Supercell return to growing its enterprise value quickly?

Along the way, we’ll point out all the product growth principles the company used to be the highest valued per employee company I have ever analyzed.

The Supercell Story

Chapter 1 - Gaming Vets

A small nation of 5.5M, Finland can fly under the radar. In Bored Panda’s survey of American geographical knowledge, not a single one of the 33 participants could place Finland on a map. Probably not a stretch for a country in which 69% of citizens cannot place the world’s top tourist destination, France.

In 1999, Finland was, in the tech world, not so under the radar. Nokia, at the time one of the world’s biggest brands and mobile device makers, was a Finnish company. This led to several mobile companies succeeding in and around the Nokia ecosystem.

Moreover, gaming is one of the world’s truly global industries. As a result, Finland had its pockets of successful game studios since the 90s. Many were the types of places that made enough money off their games to employ game teams of 10-15.

One such place was headed by Mikko Kodisoja. Together with a group of game industry veterans, he co-founded the studio Sumea.

The next year, Mikko wanted to double click into game design. A game builder at heart, he wanted to outsource all the other activities to someone else. The rest of the team agreed. So they put up a job listing for a job without any pay to start, to do everything else in the company.

The job had a single applicant, Ilkka Paananen, a senior in college. After having started college with dreams of becoming rich as an investment banker, he actually changed his mind part way through his courses. He realized that a better path to riches more suitable to his personality, instead of what everyone else wanted to do, was to become an entrepreneur.

So when Ilkka saw the job posting, he actually thought it was perfect. Here was a group of veterans who wanted to start a company. That was exactly the type of technical resource he was looking for. It is fun to hear Ilkka tell the story:

Before I finished university, I decided I wanted to become an entrepreneur. Then, I stumbled up on these guys who wanted to set up a company. That company happened to be a games company. All these guys wanted to do is develop games. And they wanted someone else to do everything else. They could not afford to pay any salaries. So there was just one applicant, me.

The group of game devs headed by Mikko took their single applicant. Ilkka was hired, without a salary, and history would ensue. Ilkka did all the non dev work.

The Sumea team was very early to the mobile space. Their first game was not only a good game, but had a strong distribution strategy. Racing Fever was considered the best mobile racing game at the time, and Ilkka and the business guys secured carrier based distribution across the world. It was quite the coup for the fully self-funded game made by a group of guys in a dark room on the outskirts of Helsinki.

In particular, the visionaries would benefit greatly from their connections with Nokia. They would grow alongside the Finnish handset maker and create several of the first professionally produced mobile games. These games helped the company live through the dot com bubble and crash. Eventually, the company grew to 40 devs. In 2003, the company made over a million euros in profit.

On the back of its success, Sumea was acquired in 2004 by the founder of EA, Trip Hawkins, new studio, Digital Chocolate. Ilkka and Mikko became rich in their 20s.

They tasted games industry success, but they were not about to stop. Both worked. Ilkka served as president and Mikko creative director until 2010. They grew Digital Chocolate to nearly 200 devs. They got to see the EA way of building games, and both also did some games industry investing.

As hardcore industry participants, they also got to see the amazing impact of the launch of the iPhone in 2007. The touchscreen made the games much more easy to play, and controls could be architected in a fun way.

Then, in 2008, when the App Store launched, they got to see the revolution in distribution. Suddenly, games were not distributed as preloads by carriers. They were downloaded by volition of the user. These seismic changes in the mobile gaming landscape would be seared into Mikko and Ilkka.

Eventually, Mikko left. And Ilkka followed shortly thereafter. Ilkka tried his hand at Venture Capital at Lifeline Ventures shortly. There he learned the power of funding teams and letting them operate autonomously. But he quickly realized that doing so as an operator would suit him better.

The two got back to talking, and decided they wanted to create a different type of games company.

Chapter 2 - A Room of Game Devs

Ilkka and Mikko teamed up with some of the other great game devs they had gotten to know in the industry: Petri Styrman, Visa Forstén, Lassi Leppinen, and Niko Derome. Petri and Visa had been with Ilkka and Mikko since the Sumea days. Lassi and Niko joined in the Digital Chocolate days. Before Digital Chocolate, Lassi worked at Remedy, another Finnish gaming success that is now a publicly traded company (valued at $500M USD). Niko had previously worked at Sulake, which had created a predecessor to the metaverse with its Habohotel.

Like most of the history up until this point, there is remarkably little about this period on the internet. Despite the number of important companies for its relatively small population, Finland tech was not nearly as well written up as American tech in that period. The best we have is a sole tweet, which has 1 like - from me.

Being a set of grizzled veterans of the industry, the founding group came together with several opinions about what the company vision should be. The team ultimately coalesced on a few key principles:

The best teams make the best games

Small and independent cells

Games that people will play for years

As a result of the three principles, and in particular the cell concept, the group decided to name themselves Supercell. Ilkka and Mikko chipped in 250K each, the Finnish government’s technology funding arm invested 400K, and Lifeline Ventures invested several hundred K. With funding in place, the team was ready to begin work.

All three of the core principles are with the company to this day. It is remarkable how that founding DNA has stuck with them. The founders had learned from their analysis and experience in the industry. The first product is still the final product today.

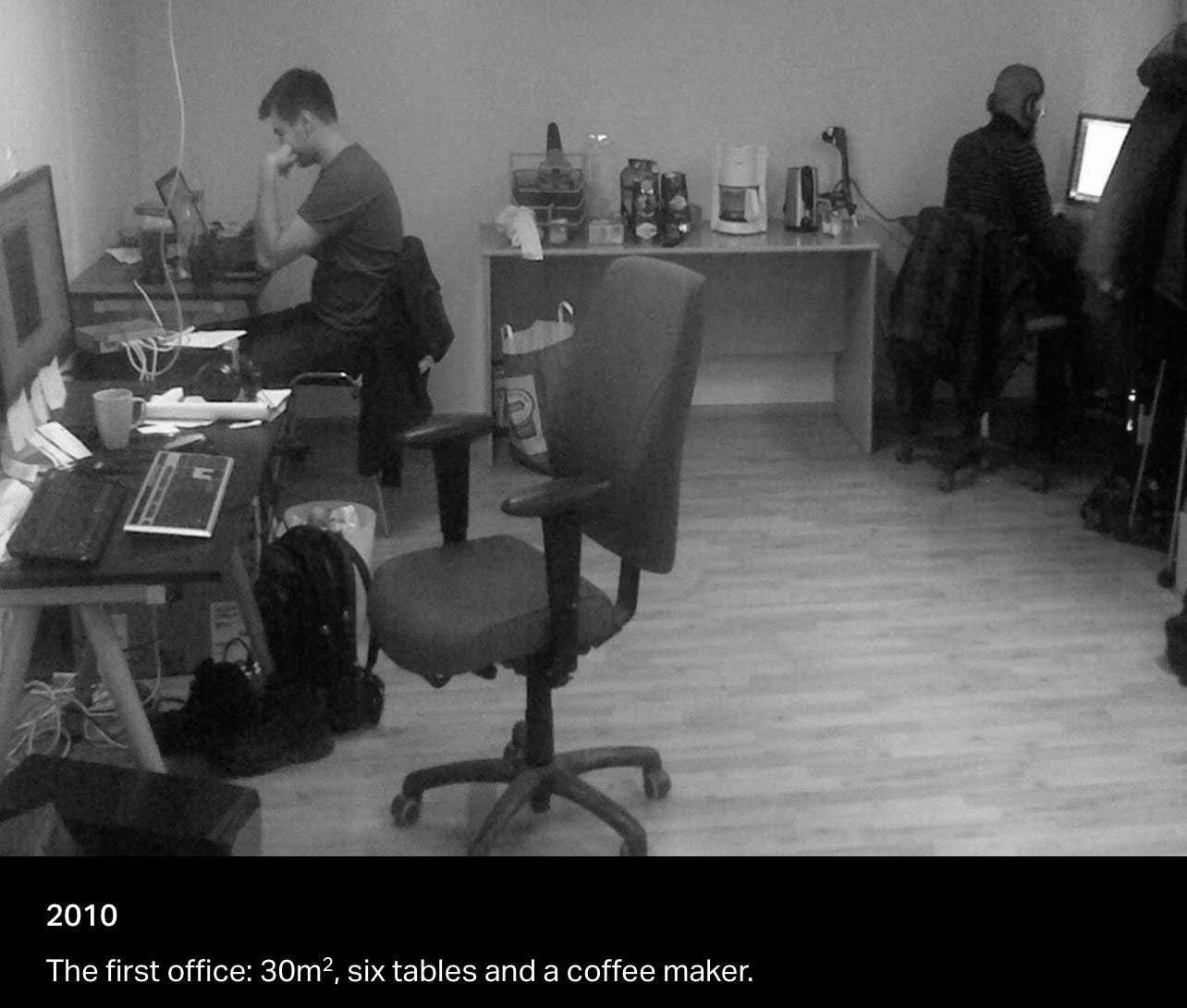

The company rented out one 30 square meter space in the suburbs of Helsinki, a place called Espoo. It’s a business suburb near Nokia’s headquarters. Furnished with six desks from a nearby recycling center, and a coffee machine, the team was ready to build.

They got to work on a game called Gunshine.net. It was a real-time massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). The devs, and the industry at large, at the time were obsessed with World of Warcraft (which had released 6 years earlier in 2004 but was still going strong). So, they tried their hand at a game in the genre.

The team started with the largest platform at the time, Facebook for desktop web. As a result, they built the game on top of Flash technology. As they were building, they had to hire more developers. When they got to 15 people, Ilkka sat on a cardboard box in another room. The team was scrappy.

The team stood up the game quickly, launching private beta in 2011. The game did well. At it is peak, it had 500K monthly active users. The game was then rebranded Zombies Online. But the name change could not save the game.

They realized that the game, although it had a lot of initial excitement, was not retaining players after a few months. It would not be a game played for decades, a key part of the vision.

In addition, it was too hard to get into the game. Players who played had played a similar MMORPG like World of Warcraft. But new players were not joining. So it could not be a mass market hit, another part of the vision.

The final nail in the coffin of Zombies Online arrived when the devs had a box of iPads delivered to the office. They started calling it, “the ultimate games platform.” Everyone was having fun with the form factor and controls. It was an, “aha!” moment for the team.

The team decided to bet the company on that insight. In the fall of 2011, they killed all the ongoing productions for Web and Facebook, including Zombies Online. The company had already begun developing several games, so it was a big decision.

The biggest hard sacrifice for the team was killing an ongoing production codenamed, “Magic.” Magic was worked on by a team of 5 day and night for six months, and everyone in the office was excited about it. It was completely new for Facebook gaming. But it was not a fit for tablets. So the team killed it.

The team made several similar hard choices. But it was the right decision. The company shifted to a, “tablet first,” strategy which shortly thereafter became a, “mobile first,” strategy.

Chapter 3 - 2 Hits In a Year

2012 would prove to be the year the small team would change Gaming history forever.

By early 2012, the company had 5 teams building games. As they learned from the Gunshine failure, they wanted to kill games that did not work early. So they killed two games in February and April, Pets vs Orcs and Tower.

One game not to get killed was Hay Day. In May, they released the game in beta to Canada. From the get go, the game was a hit. Downloads and player engagement were far better than any of Supercell’s other games. They thought they might finally have a hit on their hands.

It was a perfect encapsulation of farming on mobile. The game asked players to harvest crops, feed animals and start manufacturing. This cost them time but gained them XP. From there, players collect manufactured resources, then they sell them. This allows them to purchase new manufacturing equipment & animals, to plant more crops, and start the process over again.

The game was launched globally on June 21st. June 21st is a special time in Finland. It is Midsummer’s Eve, one of the largest public celebrations. The game was such a massive success that the entire staff had to supplement the player support team by answering tickets while on holiday. The game was that much of a success.

Today, Hay Day is still alive and well, operating as a profit center. As it had set out to be, it is a true mobile farming sim. 9 years after launch, it is still one of the best. It has had lifetime revenues of over $2B. The team has nearly hit the decade mark it had set out to. It is also Supercell’s game most played by females.

But returning back to 2012, the team was not as certain of success. However, the next game to go to beta was also promising. Built by the same team which had built the Magic game that Supercell was sad to shelve the year earlier, everyone was hopeful. The new game from the team was a real-time strategy game that had done very well on other platforms, but had not yet done well on mobile.

The game? It’s the one you’ve probably heard of: Clash of Clans. Indeed, the second important game released by Supercell that year is one of the most important games in the history of games.

Clash would have all the characteristics of a game that are now archetypal Supercell. You collect resources to build, train, & battle. Gems can either be earned or bought. And, at its core, it is the genre Supercell is best at: PvP brawler. As a brawler, the game was a bit more male than Hay Day, and it also attracted an older audience.

The older, mass audience helped the game monetize well. Players loved gems. Three months after global launch, Clash of Clans would become the #1 grossing game in the US.

The fifth game Supercell worked on that year, Battle Buddies, was axed. Like many Supercell projects, it did not have high enough retention metrics in beta.

Chapter 4 - Kings of the World

Don’t miss the rest of the story! Plus, guesses about the future, lessons for builders, and notes on the Nordic region: