🎥 Netflix: Lessons in Experimentation

A Collaboration with Productify

Product people are both lovers and haters of experiments. On the one hand, they are great at helping measure the result of changes.

On the other hand, launching anything as an experiment takes more analytics and engineering work, and typically also slows down forward progress. If you already have a vision of the future, does it make sense to test your way there in twice the time?

For Netflix, the answer has been ‘yes’ for nearly its entire quarter-century history. Since its days as a DVD mailer, through the transition into a streamer, and now content behemoth, the company has used experimentation to generate sustained levels of growth seldom seen.

Investors have richly rewarded Netflix for its culture and practice of experimentation. There’s a reason the ‘N’ in FAANG is for Netflix. The company has absolutely trounced the Nasdaq 100 and S&P500 over the past 20 years. Do you see those grey and blue lines hugging the x-axis? Yes, those are the indices:

Netflix’s product development process is a big contributor to this outperformance. As a result, for today’s pieces, we set out to answer: How does Netflix manage all the tradeoffs of experiments? Why does it believe so strongly in them?

Netflix was too difficult a subject to tackle as a lone product analyst. This is a company that takes up 15% of the global internet bandwidth, and 31% of internet television time (versus 21% for YouTube). There is a lot of surface area and nuance to cover.

So, for today’s piece, I am excited to present a collaboration with my friend Bandan, a product leader at Booking.com ($100B market cap), and before that Gojek (valued at $30B). We have been doing quite a bit of research into Netflix’s experimentation.

The Story

1997

Lesson 1: Experimentation Works in the Real World as Well as Software

Since the earliest days of Netflix, before it even began as a DVD mailing company, it has had a culture of experimentation.

By 1997, Reed Hastings was already worth hundreds of millions of dollars. He had sold his software company Pure Atria for $700M and was CEO of the new combined entity Pure Atria. One day on a commute to work with his marketing executive Marc Randolph, the two began discussing the opportunity to mail movies.

Reed saw the DVD format proliferating in Japan but had never used one himself. So he drove to the store and got himself one. He then mailed it. To his great surprise, it came back in great shape. It worked.

This little “validation experiment,” would be enough of a seed for Reed to help get Netflix started. He provided $2.5M to Marc to build out a team, left Pure Atria, and went off to pursue graduate studies at Stanford.

1998

Marc and the team went about testing out different types of packaging. The key, the team realized, was creating a low-cost envelope that protected the discs. The longer the team could extend the life of their discs, the better the unit economics.

Many of the employees' families helped test. Since DVD technology was so early at the time - 2% of American households had a DVD player - many did not even play the movies. They just shipped them back to test disk durability in the mail.

After various iterations, the team landed on Netflix’s now-famous padded paper sleeve. It was cheap and durable enough to give the team the confidence to launch.

Netflix made its official debut on April 14th, 1998. The company invented online DVD rental. Yet, just because you build it does not mean users will come. Even with a team of 30, growth would not be immediate. Netflix would experiment with hooks like free trial to nab the growing market of DVD watchers.

1999

After finishing his Master’s degree in Artificial Intelligence, Reed joined Netflix fully: not just investor, but co-CEO. He came with a few ideas.

Lesson 2: Experimentation Is Great for Business Models

After undergoing a painful layoff of one-third of the staff, one of the most successful ideas Reed and the remaining team executed in 1999 was experimenting with a subscription model.

Originally, Netflix was a single-rental service. Each rental cost 50 cents. So, the team built out subscriptions for a small alpha group. The numbers were promising. As a result, they made the change for everyone.

The new subscription tier would introduce a $15.95 per month price point for four rentals at a time. It was not just a pricing change. It was a wholesale business model change.

And, it was as close to instant success as those come in product development. Subscriptions found instant product-market fit with movie junkies.

2000

As a result of subscription’s product-market fit, as 2000 progressed, subscriptions ramped up to 95% of sales. Netflix had entered the zeitgeist. Movie lovers everywhere were subscribing to the service. This was when Reid’s work in Artificial Intelligence became especially important.

Lesson 3: Personalization Is a Great Canvas for Experimentation

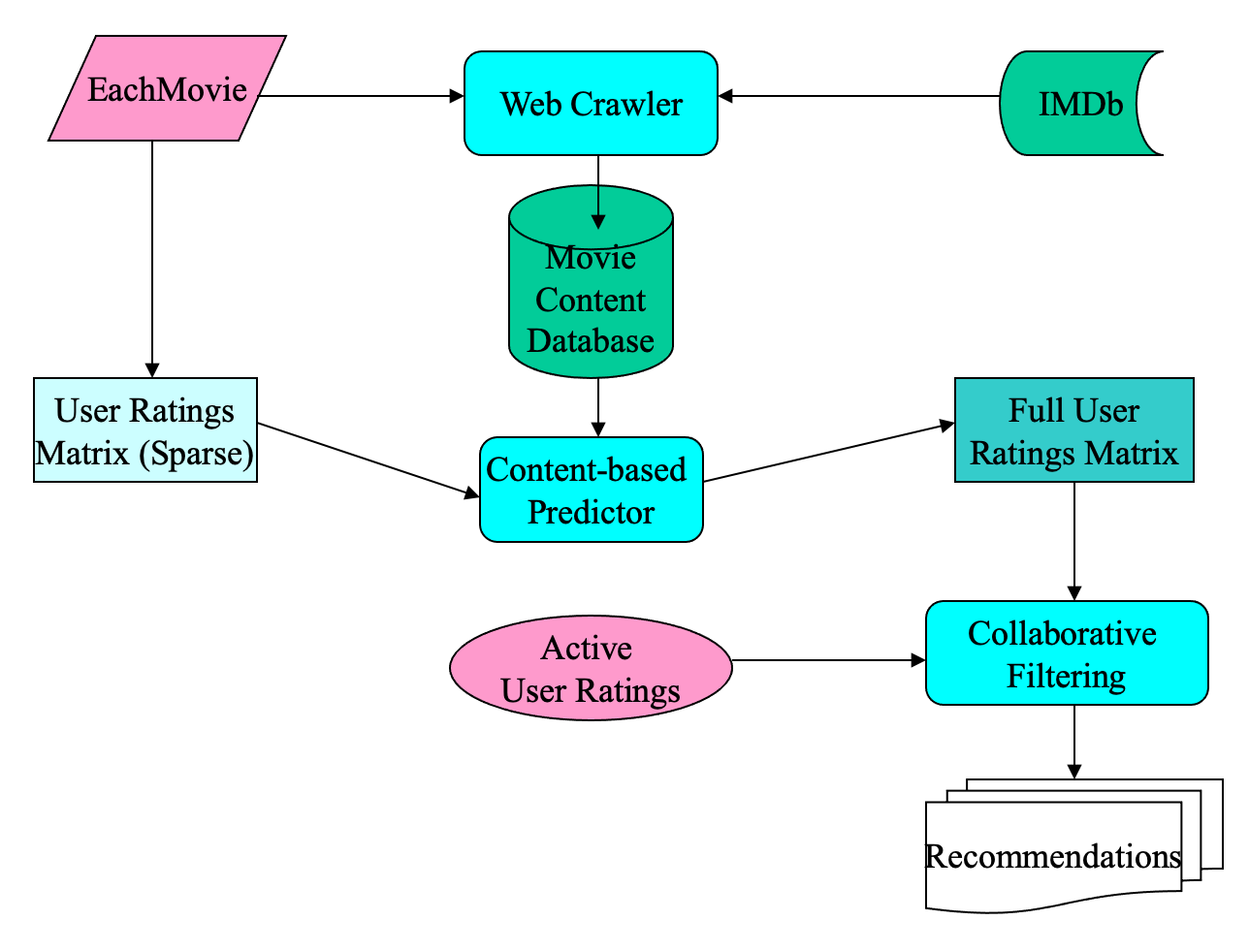

Early implementations of the Netflix system used IMDb and user rating data to create a content-based predictor. Personalization would take the content-based methods that had driven Netflix’s early algorithms and extend them to personal attributes.

These would represent a quantum leap. The earliest implementations of these algorithms used a full user rating matrix. Then, users who had rated items similarly were used to source recommendations for each other, in a process known as collaborative filtering. It is kind of like Facebook “lookalike” audiences. This generated the final recommendations:

People were watching more movies when subscribed to Netflix, getting more joy, and therefore recommending to friends. Netflix revenue more than 7x’d to $36M.

Netflix’s initiatives to combine personalization with its content model would be so successful that, by the end of the year, Computer Science classes at the University of Texas were studying them.

The only problem was that the NASDAQ peaked on March 30th, 2000. While Netflix’s revenue was rapidly increasing, its multiple was rapidly decreasing.

2001

Despite the multiple pressure, Netflix’s business thrived in 2001. Throughout the year, one of the most popular internet search queries was, “Is X on Netflix?”

It was a sign that Netflix was continuing its unstoppable ascent. Revenue 2x’d from $36M in 2000 to $76M in 2001. This consistent growth would set the stage for Netflix’s IPO, despite the consistent decline of tech stocks as the dot com bubble unwound.

2002

On January 4th of 2002, the Netflix S-1 dropped. It cataloged Netflix’s consistent growth. With investors impressed, Netflix would go public a few months later.

Netflix had a successful debut, at a $300M market cap, despite the tough market conditions. It was also, of course, a historic entry point for Netflix stock. Part of the reason Netflix has had such a remarkable run on the market is that it came out to the market in the midst of the tech bubble collapsing.

Whatever the valuation, the team would continue to work on the core business throughout this time. And the core business was personalization. Reed specifically called out work to improve search personalization in his annual letter.

When the year ended, Netflix would have 1 million accounts. Netflix benefited greatly from the shift to DVDs, with fully 37% of US households having a stand-alone player by December.

2003

Now a millionaire many times over, 2003 was the year Marc Randolph left Netflix. Reed became sole CEO.

He and the AI team continued to work on personalization initiatives across the company. And, the initiatives succeeded, wildly. Netflix would more than 2.5x its subscriber base from 1M to 2.6M over the course of the year.

This user growth would trickle down to Netflix’s financial results, with the company becoming profitable on a GAAP net income basis. It was quite the feat for a company that more than 3x’d its revenues to $506M.

In the annual report, the team highlighted two key differentiators for the Netflix product:

Movies delivered at super speed

Custom recommendations, whatever your taste

Netflix’s position in the market was one as a personalization company.

2004

This theme of personalization as Netflix’s investor positioning would continue in 2004. But the company would also be looking ahead. Streaming received a big mention, or as the company called it “alternative video delivery,” in the form of, “downloading.”

As Reed said in his letter to shareholders:

We are absolutely focused on positioning Netflix to lead this market... The winners in downloading will be the companies that provide the best content and the best consumer experience, and that’s what we do best.

2005-2006

As Netflix began to reach scale, growth slowed. Instead of 2-3x, subscriber growth hit 51% and 19%. This was still quite substantial. Netflix would end 2006 with 7% of US households as Netflix subscribers.

Part of this was a strategy. Netflix was preparing for the next leg of its business: streaming.

2007

The transition to streaming would not be without its hitches. In January of 2007, Netflix released its instant viewing feature with a few thousand TV shows and movies.

It was not the hit Netflix’s initial subscription launch was. Subscriber growth was a minuscule 19% for the year. Like DVDs, Netflix was interesting a market well before consumers. Netflix was offering a service for high-bandwidth consumers before they even had high bandwidth.

2008

Eventually, users got the bandwidth, and habits changed.

Netflix also expanded the streaming catalog to 12,000 movie and TV choices, up eightfold since instant viewing’s launch. In addition, Netflix expanded the devices one could stream from, going from a single website into hundreds of devices, including the Roku and Xbox 360.

The combination of market forces and product efforts drove Netflix’s results. In 2008, the company’s subscriber growth started to accelerate again, ending the year at 25%.

Lesson 4: People Outside Can Help

2009

As the content catalog for Netflix continued to swell, so did the costs. Reed and the team were ready to drive a broader experimentation agenda with personalization to reduce content costs.

Their solution was the $1M Netflix Prize. Released in 2006, no team was able to crack it for three years.

Finally, in 2009, the winning teams ended up submitting an algorithm that performed 10.05% better than the one Netflix used. It was a stunning example of making your data and objective clear to a wider audience to generate new experimental variants.

These algorithms were run as an experiment internally to verify, and then eventually put into production. The improved personalization helped the metrics.

Netflix would end the year with accelerating growth, growing subscribers 31% year over year to 12.3M. It took Netflix four years from 1999 to 2003 to reach 1 million subscribers. In Q4 2009, it would add that many subscribers in a quarter.

2010

Lesson 5: Build a Platform

Streaming not only changed the way users interacted with Netflix, it also vastly expanded the amount of data Netflix was receiving on its users. Now, the telemetry Netflix’s data engineers received was not simply whether someone received and returned a DVD. It also included how much they watched, when they watched, and how quickly.

Not only did the data multiply per user, the data also started coming in different shapes and from different sources as Netflix expanded into more countries. The company entered Canada in 2010.

With this multiplication of data, running multiple tests could mean that users in some platforms could experience buffering delays or subpar performance. The combination of increasing data, need for performance, and expectation of high experimentation velocity led Netflix to build a new, more robust experimentation platform. It was called Netflix XP:

Netflix XP combined data collection, statistical analysis, and visualization into an API that would connect to ABlaze, Netflix’s experimentation frontend. At the time, it was revolutionary.

First, it allowed experimentation at a scale and concurrent velocity that was not being done in many other places.

Second, it allowed data scientists to recreate any analysis from their laptops Having the ability to analyze a billion-plus rows on a laptop was unheard of at the time.

With its new experimentation platform, Netflix was able to accelerate experimentation velocity and growth. It would end the year with a massive 62% year over year to 20M subscribers. Netflix was back into hockey-stick growth.

2011

The scale enabled by XP helped give Netflix leadership the confidence to add 43 Latin American countries in 2011. It was another year of growth.

One of the increasing realizations the team came to in this period was that Netflix was used for households, not individuals. As a result, in its top 10 for you personlization row, Netflix experimented with optimizing for diversity. The first movie might be for everyone, the second for Dad, and so on. The experiment worked, and it was scaled for production.

This would kick off many years of ~30% yearly subscriber growth. The company ended 2011 growing subscribers 31% to 26M.

2012

2012 would end up representing the high watermark in terms of the raw number of movie and TV titles on Netflix:

Instead of playing the never-ending rat race of ending more content, the company began becoming smarter about what content to have on the platform. The company realized that 75% of what people watch was being driven by recommendations, so it didn’t need the huge catalog.

This focus on content quality over quantity paid off. Netflix entered more English-speaking markets like the UK and Ireland, and ended the year with over 33 million subscribers, a 27% year-over-year growth.

2013

2013 would be another year of roughly 30% growth for Netflix. There was a big strategic change, however: original content. In February, House of Cards began airing. It was Netflix’s first original series, and it launched to tremendous critical acclaim. Viewer interest was inevitable.

The show’s first season would go on to receive 9 Emmy nominations. It was a major feat for the only show that was online only that even received a nomination.

Although creative shows cannot be properly A/B tested, Netflix did at least experiment with the medium first with one big show. The show’s success proved the first validation to invest in content. Nowadays, Netflix has tripled down on the strategy and is one of the biggest spenders on original content in the world. It all started with the House of Cards “experiment.”

To get the other 5 lessons, jump over to the blog. This piece was just too detailed for e-mail:

First article I have read of the newsletter! Amazing read and yes truly believe that experimentation is a must for any product to evolve with time!