🔳 How Block Grew to $18B Revenue in 13 Years

+ 10 Life Hacks to be a Better PM

“Thinking deeply about payments.” In 2008, this sounded like the job of companies like Visa and Mastercard.

But, in the end, the company that disrupted the merchant payment experience was a small upstart.

After being fired from Twitter in 2008, Jack Dorsey came back with a new company that was thinking deeply about payments.

From the earliest days, Jack framed the enterprise in terms of social interaction. Accepting card payments and the exchange of money facilitate poor social interactions. It was awkward for the merchant to key in your amount, you over your card, then sign a receipt, only for you to throw it away.

He saw an opportunity to redesign the payment experience to facilitate that interaction. And just a few years later, the Square reader was ubiquitous. That would have been enough for most companies: one star product that redefined a market.

But Square wasn’t just about merchant onboarding. Yes, that was the first product. But Square’s larger vision was still about improving that entire payment experience and social interaction.

As a result, Square would go on to launch not only an amazing product on the merchant side, but also a starrer on the consumer side with the Cash App in 2013. Starting from a market that had been dominated by PayPal since the early 2000s, peer to peer payments, Square has expanded Cash App into a banking replacement for the underserved.

Between the cash card, direct deposit, boosts, stocks, and bitcoin, it has become a replacement for your checking account and your brokerage. Of almost any company in the US today, Square with Cash App has done the most to onboard the underserved in the financial system.

So few companies actually launch two giant products. It’s a fascinating tale, with many lessons for product people. How did Square, now Block, launch not one but two enormously successful products? Let’s find out.

Lesson 1: Find a Massive Problem

2008

In 2008, Twitter fired Jack Dorsey. The site had grown rapidly since its 2006 founding. But frequent site crashes, allegations of poor management, and enmity between Jack and Twitter Chairman, Ev Williams, led the company to let go of its CEO.

Jack took it harshly.

It was like being punched in the stomach.

But he moved on quickly. The engineer turned CEO went back to his hometown, St. Louis, Missouri. He began chatting with several childhood friends about starting a new company.

One of those friends was Jim McKelvey. Jack had worked for Jim at a publishing software company back in high school.

Jim was a Jack believer. When Jack was 15, Jim hired him. Jack wasn’t like everyone else at the company. His acuity and work ethic was at another level. The next year Jim hired people in their 30s to work for Jack.

16 years later, Jim and Jack were on more equal footing. But Jim was no longer in tech. He was actually an artist living in the city.

One day, he had worked out a deal to sell $2,000 of his glass artwork. But the buyer did not have enough cash. Jim couldn’t accept credit cards, and the deal fell through.

Jim realized that it was too hard for small merchants like himself to accept credit cards. This was especially crazy given what else his iPhone could do: everything from surf the web to play music. He shared the problem with Jack. Jack agreed it was a huge problem.

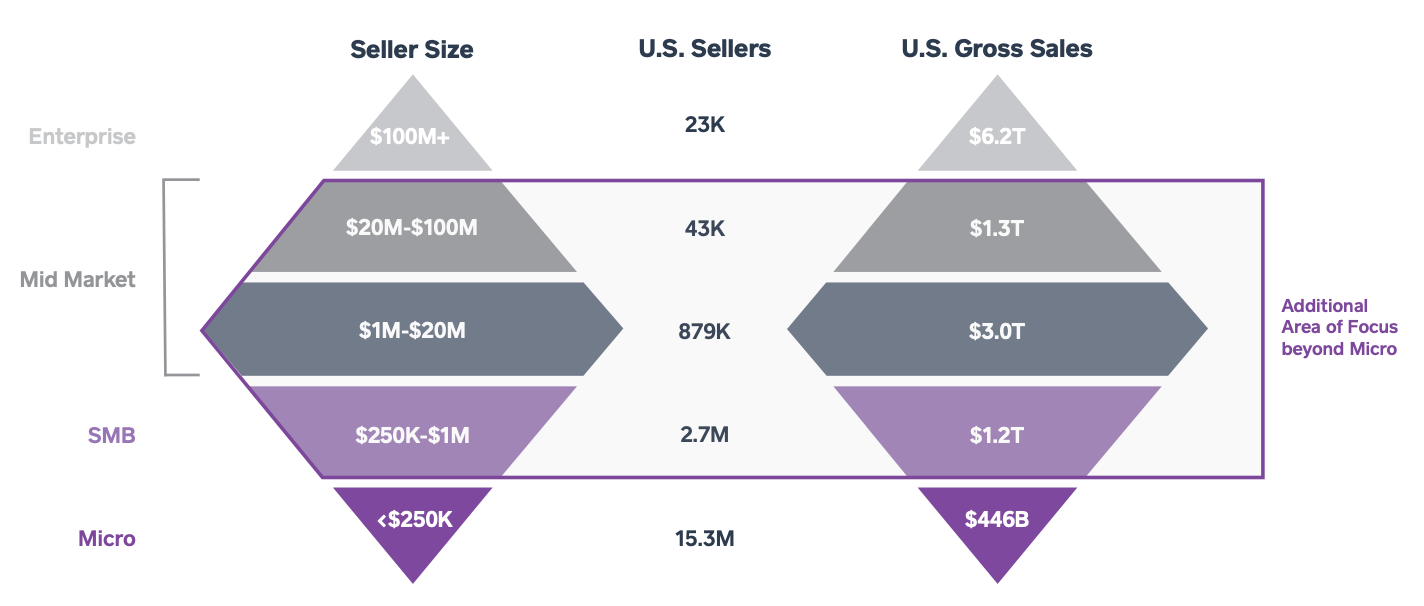

The two dived into the world of payments to learn more. They quickly realized they could service the neglected micro segment of the market. There were over 15M merchants who also had that problem. It was a ubiquitous, severe problem.

The more they looked into the numbers, the more it validated the problem that small merchants were having trouble onboarding into payments.

They got to tinkering with a solution in Jim’s home studio. They realized there was an opportunity to truly design the payment experience for merchant onboarding. As Jack said:

To really design the product experience, the payment experience, which, to my mind, no one has designed before.

Lesson 2: Make a Simple Solution

2009

In February of 2009, Square was born. Its mission: to enable anyone with a mobile device to accept card payments.

By the time Square was incorporated, Jim and Jack had created a prototype headphone dongle that would accept credit card payments. It was ingenious to design a solution with cheap components that could work through the headphone jack.

The duo went about iterating on their prototype and showing it to investors.

Naturally, investors loved it - and the opportunity to invest in the Twitter inventor’s next company. As a result, Square raised a “hyper-competitive” venture round valuing it at $40M before launching.

In a coup, the team also worked out agreements with Visa, Mastercard, and American Express to take Square payments. It was a complete card acceptance solution.

By the time Square officially launched, the first version of the product had instant product-market fit. Merchants loved that it just worked. Consumers loved that it accepted their existing payment methods.

Everyone loved that it was so beautiful. Today, the original dongle is featured in art museums.

Other companies noticed Square’s launch. But they still didn’t “get” it. When asked about Verifone’s competitor, Jack had this to say:

Square is not focused on allowing people who have merchant accounts to accept payments. It’s about allowing people to get in, immediately.

This inability for the established players to play Square’s game gave it a leg up for years to come. Square found a massive problem, onboarding people to accept payments immediately and freely, and design a simple solution that would drive its growth for years to come.

As Jack said on Charlie Rose, “It’s really complex to make something simple.” Square simplified the complex payment processing landscape for buyer and seller.

Lesson 3: Price for Growth

One of the most innovative aspects of the Square Reader was its pricing. Unlike the nearly $1000 machines merchants had to buy before Square, Square’s dongle was free.

Being $500 would have been cheap. $50 would have been mind-blowing. The Square reader was just completely free.

It was cheaper than cheap. As a result, Square effectively invented the concept of allowing micro-entrepreneurs to enter the credit card merchant economy.

Instead of a huge upfront dongle fee, Square charged 2.75% of the transaction. This was far lower than the 4% most processors charged small merchants.

It was especially cheap in light of the fact that Square gave the dongle away for free. Many of Square’s customers would just trial the dongle and never be profitable. Furthermore, of those who did try it, many would focus on small transactions where Square had to pay the card networks a per-transaction fee and actually lost money.

As a result of pricing for growth, Square had to keep its costs as low as its prices. There was no live support - no phone number to contact. As Jim McKelvey explained, this was actually beneficial. It forced Square to design innovations that removed the need for customers to reach out for support.

Pricing for growth also pushed the product team to have discipline in building solutions that didn’t need customer support. The interface was easy and elegant to use. It had few bugs or other causes for customer complaints.

One of the innovations to decrease customer complaints was fast settlement. Traditional credit card processors would pay customers after several days. Square built same-day settlement for most transactions, so merchants would get paid right away.

There was also no advertising or sales. For the first few years, Square grew squarely on the back of its innovations in merchant onboarding. Can you imagine a B2B company without a salesforce? That was Square.

2010

Of course, running a low cost business is not always smooth. As the Los Angeles Times put it, in 2010, the company “suffered from problems with its hardware and with credit processing and risk.”

To get the rest of the story - including how Square grew the Cash App into a giant and dealt with turmoil in 2010 - continue reading online. This week’s deep dive was too long for e-mail:

To summarize the article in a picture:

10 life hacks to be a better PM

Life “hacks” don’t have to be so bad. As a PM, understanding hacks can help us in our day to day jobs. From “Getting Things Done,” to “The 4-Hour Work Week,” there are things to learn.

1. GTD (Getting Things Done) Framework

GTD by filing emails, slacks, & tasks into one of three buckets: do now, later, or never. Turn off notifications for Slack and Email. Then focus on chosen tasks, without interruption. As author David Allen says, “there’s an inverse relationship between things on your mind and those things getting done.”

2. Exercise

Imagine a pill that could improve your mood, thinking, and stress levels. That’s what science shows regular exercise is. As PMs, we need to have the endurance to take on a day full of meetings & context switching. Exercise gives you the base to tackle it all.

3. Meditate

Five minutes of stillness has a transformative effect on the day. It’s like going to the gym for being present. It helps you listen and engage better in meetings. It also helps you bring a calmer attitude to the day’s work.

4. Be a giver

It may seem wise to focus on yourself at work. But as Adam Grant showed in his book “Give and Take,” the durable success stories are not takers or matchers. They are givers: people who do the right thing without expectations for anything in return.

5. Sleep well

Sleeping works wonders for thinking well, staying calm, and being happy. Trade off what you need to sleep. Making sleep a priority allows you to crush the PM work day, and not get too stressed.

6. Recruit mentors

Being a PM is all about growing. You will never be perfect at every PM skill. Mentors are like a shortcut for growth. They expose our blindspots. They pick us up when we’re down.

7. Seize the morning

Our best work is done in the morning. Block your calendar first thing. Use it to do the highest priority work. It is especially a great time for writing: detailed PRDs, strategy documents, feedback.

8. Practice gratefulness

Gratefulness helps you be happier with your current situation: you appreciate your position, you understand your employer, and you can treat co-workers with more grace.

9. Build a leveraged audience

A leveraged audience gives you the tools to do better at your job. If you post something and people point out its flaws, you can bring a better perspective to work. If there is a role that you want to fill, you can post about it and get hundreds of awesome applicants.

10. Aspire to the “4-Hour Work Week”

Tim Ferriss showed us the end result is what counts. Of course, no PM can work 4 hours a week. But automating, delegating, and freeing up time makes you happier, and better in the decisions you do take.

These 10 “hacks” don’t solve everything, but they do help you be your best “you” at work.